Nursing natural wealth

Recently, I took the time to return to the forest with a group of village leaders and teachers from the Rajabhat Institute of Chiang Mai to survey a new trekking route and visit a remote Karen village. Our leader for the trip was Mr Saichon Pruksanan, a community leader and a noted local conservationist.

We departed Chiang Mai for Mae Taeng district by pick up truck, stopped at the local market called ‘Kaad Him Taeng’ 10 kilometers from Ban Mae Malai junction and stocked ourselves with essential provisions for the trip. Various vegetables, fruit, chicken and drinking water were loaded onto the truck and after which we set off for the last part of the trip.

Saichon said previously it was very difficult for outsiders to get to the village, you had to walk seven to eight hours through steep hills and forests to reach it. I looked up towards the summit and asked myself if I will be able to reach the top without dropping dead.

“Luckily, the Forestry Department has built a narrow track. Travelling to Ban Pa Khao Larm is now a lot easier than before. But you can only get there on a four-wheel drive, but not during the rainy season,” he told us.

We stopped for lunch at the top a hill. The winter breeze was fresh and we filled our lungs with clean air. Everybody was served steamed rice wrapped in banana leaves held in place by fine strips of bamboo. Banana leaf, as opposed to Styrofoam or plastic,were the right choice because left to nature they decomposed readily without causing pollution.

After three hours of trudging along a steep slope we arrived at the village late in the afternoon. We carried our gear across the river via a cable bridge to the village. It looked distinctly a jungle settlement that reminded all of us of the old cowboy movies that had a single dusty brown trail running through it. These were houses on both sides and every house had a barn in front of it. Most Karen houses, we found out, were rather small but neatly maintained.

We were shown where we would be sleeping that night, a rectangular wooden house built on stilts with an open verandah facing the river. There were five bedrooms big enough to accommodate 20 people and three bathrooms.

The remainder of the day I spent wandering around, taking in the sights, sounds and smell of our host village. I said hello to kids who looked at us with a sense of awe and curiosity. By the banks of the river I saw a herd of water buffaloes and villagers assembling rafts for our trip the following day.

Evening came and the wind turned dry and chilly. The women in our group prepared dinner comprising fried-chicken cooked in basil leaves and spicy pork and mushroom salad. When night fell the weather turned colder. It was December. Saichon announced that the village headman will be our guest for dinner served under the soft glare from lanterns.

Mr Mana Kaw-Moo-Hae, 40, the village headman, joined us and we had a long chat over dinner. He said there were 93 Karen families in this village, with scattered settlements at the flatland around the hill. Most of them were Christian and a few Buddhist but the older generation still believe in cults and spirits. Most were farmers by profession.

It was surprising there was no electricity. “How do you live without it?”he was asked. “How can you know what’s happening in this country, especially the kids, they need to learn to grow up?”

Mana said, “We have a primary school where children learn the Thai language until grade six. We instill in our children a sense of pride at being Karen and the lifestyle we lead. You know the kids never seen a television and they don’t know what electricity is all about.”

“Several years ago I approached the provincial authorities to bring electricity to our village but they said our village was so remote tat it would be virtually impossible to run power lines across the mountains. Now we have completely forgotten about it”, said the headman, laughing, making light of the snub he received at the hand of provincial authorities.

I felt it was my turn to make a point. “Tourists come here expecting to see a village that is very authentic and typical of the hill tribe culture. They won’t be happy if they see these facilities (TV and electricity) in the village,” I said.

“Have you ever seen a Karen cut trees or slash and burn forests? We have a sense of belonging and responsibility to nature and the surroundings we live in. We are natural conservationists. We are no businessmen, we don’t know how to do business”.

“And even though most of us are Christian, the older Karens still believe in ghosts and spirits. It gives us our cultural identity, our unique place in the world. You cannot be a proper Karen, relate to our history and ancestors, if you give up spirit worship,” said the village headman.

I can’t remember how long the conversation with the headman lasted but I went to bed that night convinced that these ethnic minorities were not going to sacrifice their old values and beliefs in exchange for what we call civilization.

It was biting cold by the time we retired for the night. I had been brought up believing that it was better to sleep in light clothing but this night I just couldn’t resist helping myself with layer upon layer of clothing, and still the chill wouldn’t go.

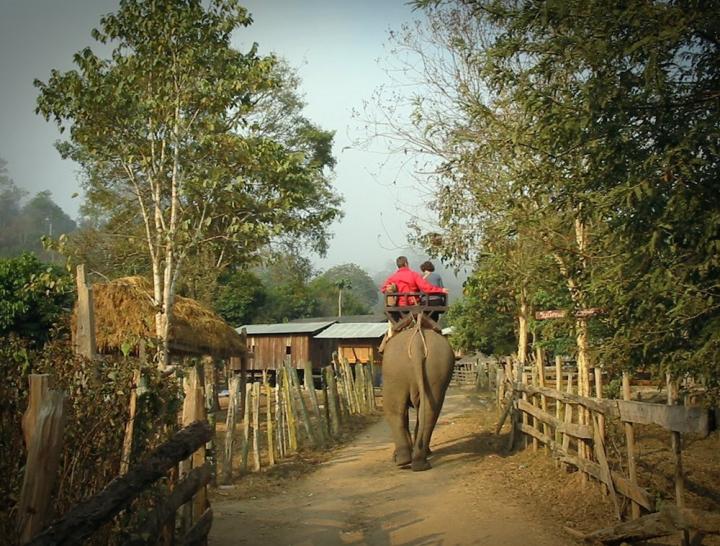

We woke up in the morning to find the water freezing cold and decided to skip the shower. After breakfast we thanked the villagers and the headman for their warm hospitality and bid them goodbye. From there we headed to the riverbank to take bamboo rafts, with Karens as helmsmen, for a bit of adventure down the river.

Each raft could carry six to eight persons including our luggage, which was is placed on a tripod in the middle to prevent it from getting wet. It’s amazing to discover how different the landscape can be than watching it from the road. Our flotilla of bamboo rafts bobbed up and down the rapids to the melody birds and the croaking of insects in the woods, and the breeze was cold but soothing to the senses.

For four hours we sailed downstream on the Mae Taeng. Rafting, though primarily there to attract tourists, doesn’t necessarily mean its soft and less adventurous or exciting. While bamboo trunks have countless applications in this part of the world, what do you do with trees felled in rain forests” Well, what a better way than to turn them into rafts and use the rafts to ferry and entertain tourists down the river.

As things turned out, it was an eventful two days that left us with an everlasting memory of the Karen way of life and a resounding ride on bamboo rafts down the Mae Taeng River. And if some one asked me if I would like to do it all again, my answer is an unqualified yes.

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian