Changing Fortunes

What a difference a year makes. In the summer of 1994, my wife Nina and I were able to tour Vietnam for forty dollars a day. A year later, with investment money, businesspeople and tourists pouring into the country, we were hardly able to get by on fifty-five dollars a day.

"What can we do?" my wife asked. There didn't seem to be any way to cut back on our minimal expenses. "I don't know," I told her. "We could always cut the trip short."

That was not an option we wanted to consider. Our hotel room in Hanoi was a bargain at twenty-five dollars a day. The motorcycle was another nine dollars. After coffee and pho--Vietnamese noodle soup--for breakfast, a Western lunch and light dinner, we'd already busted our budget without having done anything extraordinary.

"What about this?" Nina said, thrusting a newspaper clipping in my direction. The article mentioned Ba Chua Kho, a pagoda not far from Hanoi, where Vietnamese go to pray to the epistolary goddess for financial good fortune. "Why don't we ask the goddess to help us with our budget?" Nina said.

Perhaps we should have asked her to help with traffic because Ba Chua Kho pagoda is located just outside the town of Bac Ninh on Highway QL1A, the primary trade route between Hanoi and the Chinese border. Although all we wanted was to squeeze a bit more out of our budget, there were several thousand drivers who wanted to squeeze us and our Honda 100cc motorcycle off the road. No doubt many of the supplicants at Ba Chua Kho began their prayers by thanking the goddess for a safe arrival after the thirty-three kilometer trip from Hanoi.

We arrived on a Sunday afternoon. I was surprised to see that although there was parking for hundreds of cars and perhaps thousands of motorcycles, Ba Chua Kho appeared to be empty. Until we dismounted. Suddenly, from the far corners of the parking area, would-be guides and interpreters descended on us.

"Come this way," a dozen people beckoned. Refusing all offers of assistance, including that of the young man who had trailed us on a motorcycle all the way from the other side of Bac Ninh, we pressed ahead on our own.

Like Mont Saint Michel in Normandy or Main Street at Disneyland, the streets that lead to Ba Chua Kho are corridors of commercialism. In thirty small stalls, fake dollars, fake dong, and fake Chinese yuan were for sale. Incense, fruit, phony gold coins, and papier-maché candy were for sale as were flowers made of wire and colored foil. From each stall, men and women, their hands filled with bricks of poorly photocopied $100 bills, gestured for us to buy from them. To receive the goddess' blessing, supplicants must make offerings of these ersatz items.

One woman held out a cut glass tray. It, too, was fake--a poor plastic copy of the real thing. We loaded it up with $20,000 in fake U.S. money, $50,000 in fake dong, and a variety of incense and candies. I decided this was enough to mollify Ba Chua Kho and make her receptive to our relatively meager request. Unlike the Vietnamese, we weren't asking for windfall profits from real-estate deals or foreign joint ventures. We just wanted to figure out how to get by on forty dollars a day and not fifty-five.

Whether Ba Chua Kho would have been satisfied with what we initially selected we'll never know because the woman selling the stuff to us was not. She continued to stack money and incense on our tray. She would put it on the tray and Nina would take it off. A crowd gathered to watch. "Stop!" I said, finally putting an end to the Sisyphean pantomime.

In the palm of my hand I wrote "$?" as a way of getting a first price for the worthless paper and foil now stacked on our tray. In her palm, the seller wrote "40,000 dong." I didn't want to slight Ba Chua Kho by haggling over the value of what we were about to offer her, but four dollars seemed much too high. I wrote "15,000" in my palm. The woman scowled as though she had eaten bad fish sauce. I started to walk away. A dozen other vendors were waiting for the chance to overcharge us. I felt a tapping on my shoulder. "Okay, okay," the woman was saying. We paid her about $1.50 for $70,000 in counterfeit cash and climbed the thirty steps to the pagoda.

As pagodas go, there is nothing remarkable about the location, the architecture or the decorations of Ba Chua Kho. It is small and compact. As much of it seems to be under renovation as is operational. There are a few informational boards in Vietnamese but nothing in English. Nothing to let a foreign visitor know that the Ba Chua Kho pagoda is over 900 years old. Or that it was built in honor of a local woman who, through her intelligence, beauty and good deeds, came to the attention of a Vietnamese king during the Ly Dynasty. Eventually she became a princess and the treasurer of the king's fortune. Ultimately, her reputation helped her make the transition from mortal to immortal. Now Ba Chua Kho is thought of as the goddess of all treasuries, large and small.

With our tray full of offerings, Nina and I approached the central altar of the pagoda. We must have looked bewildered because instantly three older ladies took us by the hands and led us inside. They tried to explain the process to us in Vietnamese. The only Vietnamese either one of us knows is hai cafe sua ("two coffees with milk") which would have done us no good at all with Ba Chua Kho. We were forced to get by with sign language.

We placed our tray before the central altar. It was immediately apparent that what others were asking for was a lot more than a cheaper hotel room. Trays that could have easily held the giant family-size pizza at a neighborhood trattoria were stacked with all that glitters but was not gold. By comparison, our offering rated somewhere between puny and minuscule. I reached in my pocket and put a real 20,000 dong note in the offerings box.

Just as quickly I understood why the seller outside had continued to put incense on our tray even as I handed it back. There were many stations, many altars, at Ba Chua Kho, where Nina and I were expected to light and place several joss sticks. The Vietnamese placed thick bunches of smoldering incense before the deities. It was embarrassing, pathetic really, as Nina and I threaded our single strands into the sand-filled incense pots. But the ladies helping us were not discouraged or disappointed. They took us by the hand from station to station. We quickly moved past Vietnamese who were praying much more intently than we knew how. At the third station the altar was cluttered with plastic dolls modeled after cartoon characters. Individual cigarettes and plastic flowers had been left behind. There were children's toys still in their plastic wrap, now dusty with the ash of 10,000 burned incense sticks. The old ladies pulled us to the next station.

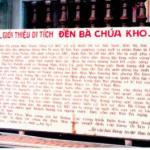

After we completed the circuit, an older man asked, in French, if we would like some tea. Mr. Nguyen Van Nguyen, the assistant director of the pagoda, sat before a wall of marble tablets engraved with the names of and the amounts contributed to Ba Chua Kho by visitors from around the world. The first name on the tablet directly behind Mr. Nguyen was the Gloss Mind Casual Wear Ltd, company of Hong Kong. I thought perhaps the people from Gloss Mind might have asked Ba Chua Kho to bless them with a better company name. Whatever blessings they received, they must have been satisfied. They had donated 1,000,000 dong.

Nina and I wanted to know about all the different aspects of Ba Chua Kho. But Mr. Nguyen, and the thirty elderly women who were attending to Ba Chua Kho that day, were much more interested in the aspects of our personal lives. A woman asked if we had children. I didn't have the heart to tell that we had been married at the ridiculously old age, by Asian standards, of thirty-seven and thirty-eight. I smiled at Nina and told the ladies, "Yes," we did have children. "How many?" Mr. Nguyen asked. "Two," I told them, not wanting to disappoint. "One boy and one girl?" Mr. Nguyen asked. I looked at Nina. Her look back was very clear. "How deep are you going to get yourself in this?" it asked. I looked back to Mr. Nguyen. "Yes," I told him, "that's right. One boy, fifteen, and one girl, twelve."

This went on in quite a bit of detail. I explained that it had been too expensive to bring the children to Vietnam. That we left them with my mother. That they were in school. All these responses brought broad, blackened smiles from the betel-chewing women who hung on every translated word. I thought I was out of the woods when Mr. Nguyen's boss, the director, Mr. Nguyen Van Lien, asked a question. When the first Mr. Nguyen translated the question into French it was something about trying to set up a correspondence between my son and Mr. Nguyen's daughter. I said something about my son speaking only English and Mr. Nguyen's daughter speaking only Vietnamese. The first Mr. Nguyen's translation wasn't entirely clear, but it seemed to be something like, "Oh, you know young people. They'll figure something out."

I was much more concerned about the plastic cut-glass tray we had left inside the pagoda than my imaginary son's social life. I had purchased all the offerings, but the vendor made it clear the tray had to come back to her. I didn't know the right word in French for tray so my explanations were more than circuitous. The closest I could come up with was something like "the flat, round, plastic thing." I was afraid the Misters Nguyen and the ladies would think we wanted our gifts back. After much discussion, one of the ladies took Nina by the hand and led her back inside the pagoda.

While Nina was gone, Mr. Nguyen Van Nguyen and I continued to make small talk. I was never exactly sure what was being communicated because I would ask Mr. Nguyen how many children he had and he would tell me how old the pagoda was. No matter the answer, I nodded respectfully, still hoping to fall under Ba Chua Kho's good graces. I still have no idea what Mr. Nguyen told the ladies I was saying but every sentence resulted in thigh-slapping laughter. When Nina finally returned (the borrowed tray in hand), she explained that with the older lady she had returned to each station and prayed in the proper manner; bowing twice with a fluid motion and then a third time with a more ragged, halting movement of the hands. After she had gathered up all our offerings she took them around the corner where, one by one, she burned them in a brick incinerator. "You burned them?" I asked her. Slapping her hands back and forth with the satisfaction of a job well done she said, "All gone." Evidently, offerings made to Ba Chua Kho cannot reach her in "the other world" unless they are burned first.

At that moment, the first Mr. Nguyen appeared with a tray filled with exactly the same things Nina said she had just burned. He explained that first-time visitors need not burn their offerings but should keep them to be burned during a return visit to Ba Chua Kho. I tried to tell him that we very much wanted all our offerings burned, but he would have none of that. When I got up and made for the incinerator he held me by the elbow and insisted that I shouldn't go.

I thought perhaps Ba Chua Kho would be supplicated if I burned some real money. I took out four one dollar bills and made for the incinerator. The ladies' smiles of approval instantly turned to waggling fingers of rebuke. Mr. Nguyen Van Nguyen gently took the bills from my hand and presented them to Mr. Nguyen Van Lien. The latter Mr. Nguyen carefully recorded Nina's and my name in a ledger together with the serial numbers of the bills I had almost burned. The two men said they would use the money in their ongoing renovation efforts at the pagoda. Mr. Nguyen Van Nguyen then filled out a certificate attesting to my donation which he extended to me, and which I received, with two hands.

After two more hours there were no more questions to ask or answer. There were no more offerings to make. It was time to go. On the road back to Hanoi, drivers seemed to give us a few more inches of roadway. Perhaps if Ba Chua Kho couldn't help us with financial fortune, she could act in Saint Christopher's stead and be our personal patron saint of travel. We covered the thirty-three kilometers back to Hanoi in a record time of only seventy-five minutes.

"I'm so glad we did that," Nina said as we entered the hotel lobby. "I'm feeling really lucky."

Days later, we learned that part of Ba Chua Kho's mystique is the pagoda's own luck. During the American war, the entire area around the temple was heavily bombed. Ba Chua Kho emerged unscathed with her reputation for good fortune greatly enhanced. In 1989, the pagoda received national historical site status.

"Excuse me, Mr. Strauss," I heard the front desk clerk say. "We have another room vacant now. Would you like to change?" I had told the staff earlier that when one was vacated, we would like a less expensive room.

"How much?" I asked.

"Seventeen dollars with air-con, Star TV, everything," he told me.

"We'll take it," I told him.

As we entered our new room, Nina tossed the offerings Mr. Nguyen had given us on the bed. He had told us to keep them for a year before returning to Ba Chua Kho. "Seventeen dollars is great," Nina said, "But next year, we're aiming higher."

That's for sure. I've already got my eye on a much larger tray.

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian