Dalat Tapestry

You sleep with the shutters flung wide, the magnificent French windows drawn in, and when you wake, early, it is to a room steeped in clean, highland air. You have been living in Saigon long enough to have forgotten the purifying rebirth that a dewy morning kindles. You snuggle for a long moment under the heavy cotton sheets, breathing deeply, savoring each cool inhalation.

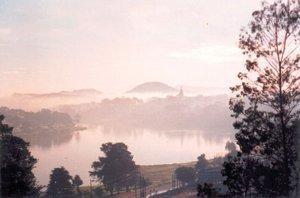

When you finally walk to the window it is with expectation, like the few giddy seconds that precede the opening of a gift. You lean against the sill. The view over Xuan Huong Lake is frosted with clouds of sweet mist that have diluted all color from the distant hills. At the same time, shadow and shape are illuminated. Grey and blue. Have there ever been so many variations of these two lonesome colors? The steam rises off your tea cup, fusing the room with the drowsy landscape.

But the sun is greedy and lifts its narcotic gaze, casting a tawny glance across the dark hard-wood floor. Its fingers are warm to the touch, melting not only the refined temperature in the room, but also the dense matte of the hills. They begin to recede. The greys become green. The blues become bold. With color comes the rest of the world. The low drone of the town is apparent. You notice a few brown needles in the tree outside your window. There are birds. A groundskeeper sweeps the drive below. Dalat awakes.

Your friends have dispersed, to play golf or to paraglide in the far hills, and the day belongs to you. You remain in the claw-foot bathtub, swimming through a limp, indefinable daydream. You wrap yourself in a white robe that hangs from a brass hook near the sink and curl into one of the damask-covered chairs. You lean back into the shadows while the bleached sunlight continues to warm the room. You read a few chapters of a good novel, but you do not give it your full attention. You do not want to take yourself too far away from this place. Eventually, you get dressed and make your way down the majestic stairs.

The Dalat Palace was built in the 1920s and has been recently restored to a style of French grandeur that even Napoleon and Josephine would have found desirable for a weekend retreat. It is late enough in the morning so that you are the only guest in the high-ceilinged dining room. You choose a table that is a mere breeze away from the doors that open onto the white stone terrace. Black, crepe butterflies hesitate in the entrance, skitter away. Through the palms and pines, down the vast slope of manicured lawn, you glimpse the lake.

You are served a plate of pineapples, apples, bananas and dragon-fruit. You break bread in honor of returning to the peaceful, familiar company of yourself, and scoop your knife into the shaved hives of butter piled in a silver dish. There is raspberry jam.

One of the many silent, solicitous waiters refreshes your coffee. You notice that it smells different here. It is not polluted by the grime and commotion of the city. It is not necessary for you to gulp it before rushing off to one of those may places that you always have to be. You hold the cup to your lips and when you finally let the liquid pass over your tongue, it is ambrosia.

As you walk around the lake, toward town, you think that you have never known a place where eclectic chalets--half Bavarian cottage, half South Pacific beach hut--wind down into vegetable gardens and flower markets. Nguyen Thi Minh Khai Street stretches flat past shops to the central market. You choose, instead, Nguyen Chi Thanh Street, a steady rise that will lead you to the peak of town. At the top you stop in a shop in Hoa Binh Square to admire the colorful blankets that are hand-woven in the nearby hills. You buy four and are prepared to leave when the proprietor invites you for a cup of coffee in the attached cafe. You were unaware of its presence, the aptly named Stop and Go. You are reminded of the weathered beach shacks that overhang the Pacific Ocean on the northwest coast.

You sit at a small table made from a slab of tree trunk balanced on two ceramic elephants. In the center of the table a horned conch shell serves as an ashtray. You look through the great pane windows down onto the market. Women in conical straw hats sell green-rinded oranges, marigolds, gladiolas and roses. You have been told that Dalat supplies the rest of the south with its cut flowers. Below, on a patchwork of corrugated tin roofs, a white cat lazily cleans its paws. The sky is overcast. Behind you a young man sits in the corner reading. The cafe is silent.

Early that evening, after a small nap and another bath, you accompany a friend back into town. It is already dark and a fragrant chill has descended. You pass families, couples, chatting quartets of teenagers. Everyone is wearing knit caps, jackets, parkas, sweaters. Nostalgically, you recall autumn at home.

You find the cafe that was recommended by another friend, the Maison Long Hoa on Duy Tan Street, just off Hoa Binh Square. The first thing you notice about Phan Thai, the owner, are his eyes, set like dewdrops of obsidian in his aging face. They glitter, and you believe he has never had a day when he has not shared laughter with a friend.

You and your friend share a dinner of vegetable soup, spring rolls, pork and rice. The food is fresh, grown and raised here. Phan Thai drifts away to greet new arrivals. They are French. It is obvious that this is his favorite language to greet new arrivals. You are not surprised. Dalat was "developed" in the early part of the century by Europeans and particularly French, who recognized its value as a retreat from the stupefying humidity of the Mekong Delta.

A woman stands on the sidewalk with a large basket strapped to her back. Your friend purchases the blankets that were hand-woven by her father. When he returns you finish your meal. You observe that the two men at the table next to you are drinking a pale pink liquid from cordial glasses. Your friend asks what it is.

"Strawberry wine," Phan Thai says. Among its other natural resources, Dalat is famous for its strawberries. "It is homemade, by my wife. This bottle is three years old." He shows you the business card of a winemaker in France who praised his wife's vintage. He tells you the name of an exclusive restaurant in Saigon whose manager purchased twelve bottles the last time he was there.

You order two glasses.

You are from the United States. Your friend is from Australia. Phan Thai stands over you and toasts the hospitality that your nations have shown to his countrymen over the years. You feel humbled.

But Phan Thai is already onto another track. He asks if you know who John F. Kennedy was. "His son has eaten here. Twice. With his girlfriend."

"Which one?" you ask, laughing.

Phan Thai says, "I wanted to take his photograph, but...I must respect." You understand. It is exactly because of this that people return to the Maison Long Hoa, the reason they recommend it to friends. This is not the sort of place where you come to see and be seen, as many notorious destinations are. Before you leave, your friend buys two bottles of strawberry wine.

You escort your friend across Hoa Binh Square to the Stop and Go. You have not been sitting there more than a few minutes when Duy Viet, the cafe's owner, brings his friend Vi Quoc Hiep to your corner. Vi Quoc Hiep owns an art gallery on Tran Phu Street. Duy Viet produces paper and pen. You sit, upright, like Mona Lisa, trying not to grin, while Vi Quoc Hiep squints, sketches, and finally renders...you...sitting stoically in the Stop and Go. (How much did he charge you, friends ask later, and you frown at their cynicism.) Duy Viet examines the drawing, critically, pronounces it a good likeness, asks why you didn't smile, then takes out his ink brush pen and adds, "Two blue eyes, what a surprise." He hands it to you. "A souvenir."

Vi Quoc Hiep must leave and Duy Viet takes his seat. Your friend asks if he would like to share some strawberry wine. Thimble teacups appear. You toast life. Duy Viet and your friend talk, quietly, their conversation absorbed into the soft old wood, while the town below is slowly stolen by the returning mist. Duy Viet sketches one of his poems for your friend to take home. The lights sputter and then fade. Never has one of Vietnam's many blackouts been more appropriate. Duy Viet lights one red candle for each of the three tables. When he returns, he carries a bottle of mulberry wine which he uses to toast in the wake of the strawberry.

"Do you play?" asks your friend, pointing to the guitar

"A little."

And Duy Viet fills the flickering night with a familiar, haunting flamenco that has befriended many a stranger in many a shadowy cafe around the world. You lean into the room, cradling your teacup, and another of Duy Viet's poems comes to you:

As a wind-orchid

I'm living in bluish mountains

high in the Highlands

Covered with clouds and fog

throughout the year

Carefree as a breeze on

a Fall day

elating confidences for

Myself to hear

By a winter's night, blooming

while the moon starts

rising to welcome Spring

The Fragrance of

wind-orchid

wafted high

in the Breeze

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian