Cambodian Dreams Deferred

They say that to understand all is to forgive all. And on the 29th of January 2003, Cambodian mobs in Phnom Penh looted and destroyed Thai-owned businesses and set fire to the Thai embassy. The Thais cannot yet forgive because they do not understand. Some say that the Cambodians were enraged by a Thai actress's alleged suggestion that Angkor Wat belonged to Thailand. Others suggest that the Cambodians were releasing years of suppressed resentment toward their stronger neighbor. Still others believe that the riots merely served some shady domestic purpose, perhaps to fortify the power of incumbent leader -- and former Khmer Rouge cadre -- Hun Sen.

Whatever their causes, the riots were proof that all is not yet well in Cambodia, which in the past century was one of the world's most ravaged and pitiable states. In a sense it is miraculous that Cambodia continues to exist at all (though some would argue that because the Vietnamese installed Hun Sen following their invasion, the country remains a Vietnamese puppet.) Angkor Wat has been under nominal Thai control before: first with the collapse of the Khmer Empire, and most recently as a result of cessions by Vichy France during World War II. Then again, the Thai city of Lopburi -- as evidenced by its ominously beautiful Khmer temples -- was once a part of the Khmer Empire, as were portions of southern Vietnam, known to the Cambodians as Kampuchea Krom.

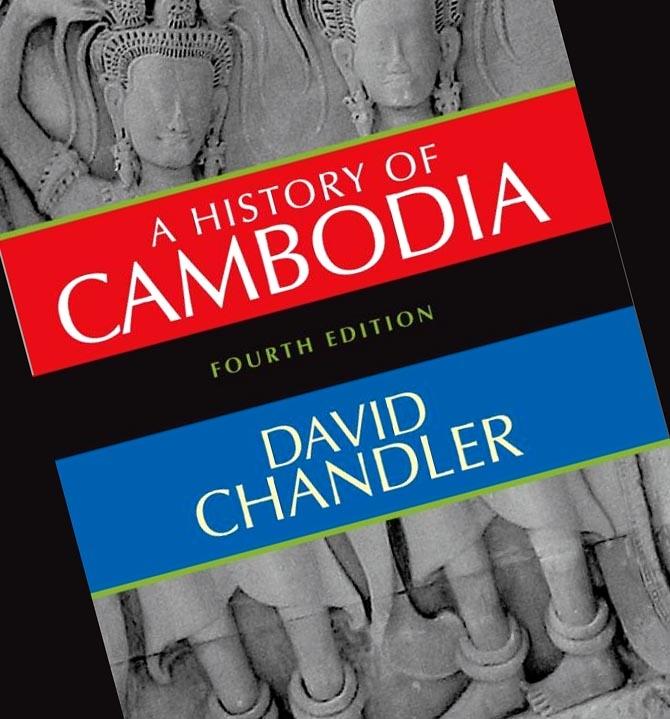

History, in other words, has not yet come to an end. And as David Chandler argues in his exemplary /A History of Cambodia/, Cambodia cannot accurately be described as "timeless" or "unchanging", despite the many compelling reasons to do so. Certainly in some respects the life of the average Cambodian has changed very little since Angkorean times: Chandler writes, for example, that a Chinese envoy's description of "rural marketing" in 13th century Cambodia "could easily have been written about Cambodia in the 1990s." All the more reason for the events of the past half-century to have been so traumatic, as the country abruptly confronted the worst of nearly one thousand years of human development.

If you believe that history is determined more by principle than by power, then there are many things in Chandler's history to be angry about. For example, that the United States gave tacit approval of China's 1979 invasion of Vietnam, when ostensibly one of the main purposes of the Vietnam War had been to prevent the expansion of Chinese Communism. Or that, as Chandler writes, the Americans "dropped nearly twice as many tons of bombs on rural Cambodia as they had dropped on Japan during World War II" -- despite the patent lack of targets. (Chandler writes of the bombing that "no estimate of casualties has ever been made". This is no longer true: Yale scholar Ben Kiernan puts the figure at 150,000 civilians.) Or that among the Khmer Rouge's supporters were Thailand, China, and the United States, simply because the Khmer Rouge had picked a fight with Vietnam: the enemy of an enemy is a friend. And once this axiom is admitted, Cambodia's recent history (among Chandler's other books is /The Tragedy of Cambodian History/) is easily deduced.

In some ways Cambodia was ripe for conquest. Although Chandler dismisses the terms "feudal" and "Oriental despotism" as accurate descriptions of Cambodia, its rulers have always been quite arbitrary and the Cambodians without voice. Indeed, Chandler argues that Angkorean king Jayavarman VII's "break with the past, his obsession with punitive expeditions, the impetuous grandeur of his building program, and his imposition of a national religion rather than his patronage of a royal cult all have parallels with recent historical events". (At Angkor Wat Cambodians sell high relief prints of Angkorean kings sitting in state before an audience of fawning subjects. The scene is perhaps intended to recall Cambodia's departed glory; but to the initiated it seems only to glorify tyranny.) In pre-Angkor Cambodia, writes Chandler, "Evidence from inscriptions suggests that slaves of various kinds made up the majority of the Cambodian population at any given time." And though the Cambodian "slaves" encompassed everything from chattel to debtors to dancers, Angkor Wat itself is a monument to some inhumane system of organized labor existing at a time when, for example, English barons were handing the Magna Carta to King John. Autocracies are inherently unstable. And Cambodia's geography lent itself to invasion: "Unlike the other countries of mainland Southeast Asia," writes Chandler, "Cambodia has no mountain ranges running north to south, providing barriers for east-west penetration. Low ranges of hills mark off its northern frontier and parts of its frontier with Vietnam, but these have never posed serious problems for invaders."

The French "rediscovery" of Angkor Wat in the 19th century, combined with the French exhumation of Khmer history, did much to restore Cambodian national pride (and French protection and technology led, says Chandler, to an astonishing quadrupling of Cambodia's population). But this led to the fanciful notion that modern Cambodia could once again be as strong as Angkor had been. The Thai claim of ownership over Angkor's ruins is no more absurd or provocative than Pol Pot's claim of ownership over Kampuchea Krom, or Burmese journalists' use of the term "Yodya" to describe Thailand (the Burmese infamously laid waste to Ayudhya -- "Yodya" -- in 1767.) Each of these countries has convinced itself that it is a direct descendant of some ancient empire, but too often this is only a rationalization for bullying, resentment, war, or a false but expedient sense of national unity. For there remains disagreement about the origins of these so-called ethnicities: a Chinese visitor to ancient Cambodia wrote that its "subjects are ugly and black; their hair is frizzy...." Was he simply recording Chinese preconceptions about the appearance of "barbarians"? Maybe. But certainly many Southeast Asians would shudder to think that they or their ancestors fit this description. According to Chandler, a Khmer (originally Indian) myth has it that the Khmer are descended from "a foreigner and a dragon-princess, or /nagi/, whose father was the king of a waterlogged country." How ironic that a country so prone to xenophobia in times of crisis should trace its ancestry to a foreigner!

Cambodia is a lovely country; and travelers to it commonly honor the gentleness of its people. But much of its history is the stuff of nightmares. And the recent riots, while their significance should not be exaggerated, seem to show that the dawn is not yet come.

Review of David Chandler's A History of Cambodia, Silkworm Books, 1998.

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian