Double Lives: The Siamese Twins' Story

Because of their brotherly bond made flesh, and their astonishing, perfectly synchronized acrobatics, like walking on their hands, the twins were billed as the "Eighth Wonder of the World" after they arrived in New York at the age of 18. For the next decade, they performed for packed houses all over America and Europe on bills with other human oddities, such as the "Amazing Wolf Children of Australia." The legendary showman PT Barnum managed them; Melville immortalized them in Moby Dick; and it's said they put on private spectacles for Queen Victoria and Russia's Czar Nicholas. Although they shared no internal organs, and were often derided as a fraud, Chang and Eng were actually joined below their breastbones by a ligament about eight-cm's long and four-cm's wide. Already wealthy before they turned 30, the twins tried to retire to a family and farming life in the American south, which would soon be torn apart by the Civil War.

In recent years, their dramatic, mutual history has been the catalyst for two much-lauded literary novels, Chang and Eng by Darin Strauss, and God's Fool by Mark Slouka. The brothers' rags-to-riches upbringing has also opened quite a few tear ducts in at theatres in Singapore, China, and Malaysia. As a result, the steady trickle of foreign visitors to their hometown in Samut Songkhram city (70km southwest of Bangkok) has become torrential.

Much of their early lives is still a matter of conjecture. Both the musical, and the two novels, document their actual birth, however, in a floating home beside the Mekong River, during the rainy season of 1811. If the old floating homes have long since been replaced by a Caltex refinery and some fish sauce factories, traces of the maritime life Chang and Eng once led (their father was a fisherman) are still very much in evidence. Head down the riverside roads by the Mekong Bridge, near where they were born, for glimpses of fishing trawlers. In the shipyards, workmen - pounding, polishing, and patching - cling to 10-metre-high scaffolds of bamboo hanging from the sides of trawlers. And the stench of rotten fish made me squint.

A few kilometers north, past prawn farms and ornate temples, is Don Hoy Lot, where the Mekong meets the Gulf of Thailand. Alongside the banks are enormous wooden restaurants up on stilts. The seafood is as famous as the crab-eating macaques who, around dusk, scamper across the mudflats in search of their staple diet.

As children, who were ethnically Chinese, the twins were jeered and taunted endlessly by their peers. Worse, much, much worse, is how they were blamed by superstitious Siamese for causing a cholera epidemic which claimed 30,000 lives. In the Singaporean production, Chang and Eng: The Musical, the song "Living Curse" sounds off about their frightful ordeal. And what sustained them in their most despairing hours? In the opinion of Ken Low, the musical's composer from Malaysia, it was the unconditional love of their mother. This motif has played well in Asia: The musical is the longest-running theatrical work in Singaporean history, and also the first English-language musical ever staged in China, back in the late 90s when, the composer says, "We were treated like rock stars."

Ken is skeptical about whether or not these filial motifs will be mocked as melodrama if the production finally makes it to Broadway and London's West End. "Chang and Eng's constant longing to see mom again may not sit well with Western audiences. In Asia, we all live in the family unit until we get married, and sometimes we don't even leave home then," he laughs. On the other hand, he believes that Asians living abroad may well find the twins' difficulties in adapting to life in their adopted country while yearning for a homeland they would never see again gives the play some contemporary relevance.

Duck Farmers

Today, every Thai person knows who the Siamese twins are. But in Thai they're known as Injan. It's an auspicious name, meaning "Earth-Moon, but it does lead to the common misconception that they were one entity. Not so. The brothers had much different demeanours. Chang, who usually stood on the right, was gregarious and playful, whereas Eng tended to be more withdrawn and studious.

In Thai history books, children learn that the brothers were the most cherished performers in His Majesty King Rama II's Royal Court. Renowned as a patron of the arts and comedy troupes, the monarch often had them perform at the Grand Palace in Bangkok. It has been speculated that his patronage kept them alive. One obvious bond they shared is that King Rama II was also born in Samut Songkhram, the country's smallest province. And his memory is memorialized by the lush park and florid, botanical gardens named after him in the provincial capital.

As adolescents, Chang and Eng helped provide for their hard-luck family by raising ducks and selling their eggs. Bigger than chicken eggs, and with a reddish yoke, duck eggs are still a crucial ingredient in the piquant, seafood salad called yum, in rice porridge, and, when mixed with coconut milk and sugar, in many Thai desserts. The brothers would've also known how to make one of the province's specialties - "thousand-year-old eggs." To preserve their freshness, the duck eggs are boiled in salty water, and left for a week to soak in the water. Then they are wrapped up in rice husks and earth, and left in a box for up to a year. Even today, local fishermen will take a good supply of them on long journeys for a welcome dose of protein.

Ducks are still a common sight on many of the province's canals. Like the one where we stayed in an old-fashioned, Siamese-style house with a verandah overlooking the water, and a roofless shower outside, which was overhung by the green, cannonball-sized fruits of a pomelo tree. This is one of the "home-stays" run by local families in the Amphawa District. Along with appetizing local meals, Moo Bahn Song Thai (call 034-717-510, but speak slowly in English) also offers boat tours of a floating market, fruit orchards, temples and a nocturnal outing to watch fireflies turning themselves on for mating. Even without booking a tour, all I had to do was sit on the porch and watch a portal into the past open before my eyes. In the early morning, full of birds gossiping and fish splashing, monks in saffron robes came paddling down the canal, just as they have for centuries. The Buddhist faithful congregated on piers to put plastic bags of food in their alms bowls. Only a short time later, a wizened old woman in a conical hat paddled by to serve us steaming bowls of noodles right on the waterfront.

After breakfast, I asked my traveling partner, Anchana, if she'd learned in any Thai history books about how the twins had married sisters in North Carolina, adopted the surname of Bunker and sired 21 children. She looked quizzical. And of course wanted to know how they'd been such studs. So I fetched a copy of Darin Strauss' novel, Chang and Eng, which has been praised by writers as diverse as James Ellroy and Joyce Carol Oates. A middle chapter entitled "The Mysteries of the Bridal Bed" details how the twins lost their virginity. After their wedding in 1843, the conjoined brothers agreed that when one of their wives was in bed with them, the other brother would go into a trance and try to be "mindless".

When he was sleeping with Sarah for the first time, Eng thought, "I felt my wife had become a strange part of me, not integrated fully - but not fully only because this new part of me was experiencing its own pleasure. In my hand, her hand, trembling and weak, her fingers hooked around mine - and the only way to describe what I experienced is as a new-sprung void in my chest, sucking out a solitary life's worth of loneliness and wanting now to be filled with something new."

Museum Of Curiosities

Anchana's next question was whether their children were normal or not?

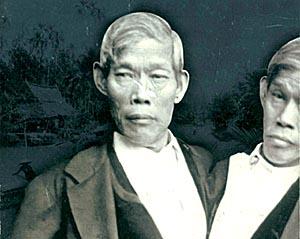

Judging by the photos on display in the museum devoted to the Siamese twins, the answer is yes. It's located around four km from the center of Samut Songkhram city. Outside is a statue of them and a full-scale replica of their floating home. Inside is a shabby exhibition of old photos and lithographs. Thanks, however, to a visit by their distant relatives last year, and a promise of additional funding, said architect Panya Langlawsee, the museum is going to undergo extensive renovations.

Whatever its shortcomings, the gallery of fading images provides some touching glimpses into the twins' personal and professional lives; their wives, their children, their former manager PT Barnum, and their old posters are all on display. The portrait of their two lovely daughters - Eng's Kate, who looks Asian, and Chang's Nannie, who looks American - is particularly heartbreaking when you read the caption about how both of them died of TB at the age of 27. Of interest to the true sideshow connoisseur are the promotional photos for the final, disastrous tour they undertook in 1866 after the Civil War devastated their farm in North Carolina and their slaves were freed.

For many visitors to the province, and us, the real voyage of discovery was the evening boat ride to see the nesting grounds of fireflies. Motoring along the dark canals with a fan of light illuminating derelict houses on stilts and bats swooping across the water under foliage so thick that it blocked out the sky and moon was a trip into the heart of darkness. And the trees, blinking on and off with thousands of fireflies making quicksilver flashes, are permanently branded in my memory banks.

On the way back to our canal-side hideaway, I imagined the two young twins watching a similar mating spectacle some 180 years before me. Then I recalled the ending to Darin Strauss' novel. In spite of all the bad blood between them, partly caused by Chang's alcoholism and Eng's embitterment, when Eng woke up in the middle of a cold January night to find his brother dead beside him, the final act of his life was witnessed only by his wife Sarah.

"He twists away from her - he draws his brother closer to him. Eng takes his twin into his arms: This is the image Sarah keeps of her husband for the rest of her life. Eng dies."

An engraving on the side of their statue outside the museum shows that even in death they could not escape the morbid voyeurism which had always haunted them: Their corpses were sent to a hospital in Philadelphia for an autopsy; and the doctors made a plaster cast of them. But the brother's bond, which helped to bring them from the banks of the Mekong to the royal court of King Rama II, and onward to infamy in the West and a double coffin in North Carolina, was not severed.

- The End -

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian