Hoi An Hoard, Part One - The Excavation

During the 15th century, off the Hoi An coast of Vietnam in the South China Sea, a trading vessel filled with porcelain vanished without a trace. Five hundred years later, in 1999, as a storm swept toward this very same area, the archaeological excavation barge Tropical 388 was confronted by the possibility of a similar fate.

The divers working out of Tropical 388 were attempting to retrieve artifacts from the wreckage of the trading vessel, a procedure that was hazardous under the best of conditions. By no means were these the best of conditions. The shipwreck was located in the middle of a typhoon zone known as the Dragon Sea.

The storm was detected 1,500 miles away, but these were men on a mission -- to rewrite a crucial chapter in the history of Vietnam. They were accustomed to obstacles, and they forged on, bracing themselves against the swells that were battering Tropical 388, until it was obvious that the tempest was heading straight for the dive site.

Down below, the divers struggled to return to their diving bell. "The bell was bouncing up to six feet off the seabed," says Ong Soo Hin, the president of the salvage company. "The divers go in and out of the bell through the bottom, so you can imagine how much trouble they were having at this time."

This was the second typhoon that the expedition had experienced. The first had been harrowing, but at the time the divers were using surface methods. Now, they were living and working inside a pressurized cabin and diving bell. This innovative technique, scientifically orchestrated to acclimatize the human body to the shipwreck's depth of seventy meters, meant that the divers could not simply be yanked to the surface and released into the fresh air.

It took six hours for the divers and their underwater connections to be locked into the pressurized live-in chamber on board Tropical 388. Even then they were still at the mercy of circumstances beyond their control. The transition from the chamber to a normal surface environment required a three-day depressurization process. Despite the churning meter-and-a-half waves, the divers could not leave their cabin. To emerge without undergoing the proper procedures would mean instant death.

All six divers were transferred into a pressurized rescue chamber. In the worst case, the chamber would be jettisoned. Adrift in the sea, the divers would be able to survive for a day and a half. It was hoped that this was enough time for a storm to pass and a rescue team to arrive.

To outsiders, this may have seemed like an extreme precaution -- the rescue chamber was a cramped space that could offer no relief from the typhoon raging outside -- but it was one that could not be excluded. In the midst of a storm on another salvage operation in 1996, a pressurized cabin came loose and flew overboard. It sank and drifted, and all of the divers suffocated.

This may have been an expedition constructed on a teetering foundation of risks, but trepidation was not allowed to factor into the operation's progress. As soon as this typhoon passed, the divers returned to the wreck. The team's willingness to participate at all costs signaled their belief in the significance of this particular treasure hunt -- the possibility that a few bits of ceramic found drifting in the sea would result in one of the greatest underwater archaeological discoveries of all time.

In the early 1990s, in the waters surrounding Cu Lao Cham Island, fishermen trawling for squid and red snapper began finding broken porcelain ensnared in their drift nets. They took the shards to the nearby town of Hoi An. This ancient trading port in Central Vietnam is now a sleepy town whose main street is lined with shops that cater to a steady tourist trade. The merchants who examined the pieces quickly realized their value.

Vietnam has strict laws prohibiting the export of national artifacts, and the unpublicized nature of this find paved the way for the sowing of a lucrative underground trade. But the secret was too good to be kept, at least in commercial circles. Middlemen drifted into town, professional dealers got involved and pieces began to show up in antique markets in Saigon, Singapore, Tokyo, Hong Kong and London. One piece made it all the way to New York City.

By 1995 an avaricious demand inspired an activity that could have led to the total destruction of all remaining intact artifacts. Nets dragged through the sea were no longer snagging loose objects. Because the wreck was so deep, diving was not feasible. Greedy looters devised a way of dragging steel rakes over the site in hope of dislodging porcelain from the wreck mound. This method was massively destructive, but those involved didn't care. They were getting exactly what they wanted -- new pieces to sell.

Throughout this whole process, scholars and other experts in the field had been hearing rumors of the existence of a newly discovered, archaeologically significant cache, but they were unable to flush out its source. The negligent raking might have continued until the entire collection was either destroyed or sold off were it not for a pair of greedy Japanese art dealers who were stopped at the Da Nang Airport. Their suitcases were loaded with contraband pottery.

Although the exact location of the source of the ceramics was still a secret, this was the break the authorities had needed. They traced the porcelain back to the Cu Lao Cham Island region, and from there they honed in on the general vicinity of the wreck site. The question now was how to deal with this newfound information.

Vietnam's coastal waters are an aquatic graveyard. Reports of shipwrecks -- from pirate ships and Spanish galleons to British, Dutch and French trading vessels -- have been circulating since the early 1600s. Many were not worth the effort and expense that an official diving operation entails. Others exceeded all expectations.

Just a few years earlier, while cruising near Con Dau Island, south of the coastal resort town of Vung Tau, a local fisherman snagged a lump of iron that contained several fragments of porcelain. His catch led to the recovery of a Chinese junk that was dated at 1690. When the cargo from this ship was auctioned at Christie's in Amsterdam in 1992, it brought in over seven million US dollars.

Cases such as the Vung Tau Wreck contributed to the compelling argument for serious investigations into the recent find. The Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of Transport and the Vietnamese History Museum were consulted. According to Mensun Bound, Director of the Oxford University Maritime Archaeological Unit (MARE), scientists and scholars cannot afford to deal with such a shipwreck without commercial involvement, and so the decision was made to authorize the Vietnam Salvage Company (VISAL) to undertake initial exploratory dives. Lacking the capabilities for conducting a thorough search at a depth of seventy meters, VISAL contacted the Malaysian salvage company, Saga.

Saga had been working with VISAL on a project to recover tin ingots from a WWII wreck in Da Nang. VISAL knew that Saga would be able to provide the financial resources, state of the art diving equipment and necessary expertise for this kind of deep underwater work. Together, VISAL and Saga submitted a proposal to the Vietnamese government asking permission to jointly assess the area and locate the wreck. Saga would bear all costs. In return, if the survey proved fruitful, the government would grant Saga exclusive excavation rights.

Saga's government-sanctioned exploration began in mid-1997. Under the supervision of Bound and local archaeologists, they began searching for the wreck. By June, side scans, which bounce sonar waves off abnormalities, verified an "anomaly" on the sea floor. But when a video camera mounted in a Remote Operated Vehicle was sent down to take photos, it malfunctioned.

Frustration was setting in. Money was running low. And in a desperate and reckless move, two of the divers decided to dive off a fishing boat to investigate the wreck. Because they would not have access to a decompression chamber when they surfaced, they were putting themselves at the grave risk of nitrogen narcosis.

When nitrogen is breathed under extreme pressure, it saturates the nervous system. This can happen when a diver ascends too quickly and doesn't undergo the crucial decompression process. Normal functions become impaired, and effects range from numbness or feelings of euphoria to convulsions or unconsciousness.

To compensate, the divers created their own makeshift decompression system. They hung air tanks at different depths so that they could surface gradually without running out of air. Their scheme was resourceful, but the result, ultimately, failed. One of the divers couldn't reach the sea floor. The other made it, but his camera caved in under pressure and he was unable to determine what he was looking at.

Eventually, a remote controlled camera was maneuvered into the wreck. No one on the crew knew what to expect, and the safest bet, to stave off disappointment, was to prepare for the worst. The looters had raised an estimated extraordinary 50,000 to 70,000 pieces, and it was not unreasonable to assume that they had done irreversible damage.

At first, it seemed as if this fear was true. There were fresh breaks in everything contained in the upper layers. But as the camera continued to roam the shadow depths, it eventually revealed an incredible sight. Behind a veil of dark, murky water were rows and rows of porcelain.

"The dishes and rice cups were stacked as if in a market," says Bound. "We found one nest of six circles, the same as can be found in Vietnam today. We found smaller, more delicate pots stored within larger jars."

The wreck was intact, and the prospect for a full-fledged recovery had become a reality. That is if the crew could figure out a way to pull it off. Relics had been retrieved from greater depths, using cherry pickers to pluck artifacts from the seabed, but the enormity of the contents of this wreck required a more efficient approach. Bound and his colleagues began plotting the deepest, full-scale archaeological excavation ever attempted.

Zero visibility. Raging currents. Freezing cold. Collectively, they were the welcome wagon that greeted the excavation team when it launched its operation in the late spring of 1998. Still, the group was optimistic. It determined a technique that seemed ideal considering the limitations inflicted by the location of the wreck. By using a surface-supplied mixed gas system, topside archaeologists would be able to directly supervise the activities of twelve divers and debrief them after each dive.

Quickly, though, it was realized that this method was riddled with disadvantages. Divers were able to stay on the seabed for only thirty-five minutes at a time. This made it impossible to conduct uninterrupted underwater work. It also meant that the divers must spend three hours in a decompression chamber daily. Added to these complications were out-of-season storms that culminated in the first of the pair of typhoons that had attempted to wipe out the entire expedition.

It arrived without warning. According to Bound, "The ship stirred, the anchors tangled, and slowly it began to edge over on its beam end. Grown men were crying. They were down on their knees praying. One man was rigid with fear. We sounded the claxon to abandon ship, and we cut through the anchor lines. Somehow, the ship righted itself. But we were completely wiped out." The operation was halted for reassessment.

Rather than give up, the team returned with an extraordinary proposal. For the first time in underwater excavation history, they would employ a technique known as "saturation diving." It would no doubt prove to be the most effective approach. It was also undeniably the most dangerous, since it required that the divers' tissues become saturated with an artificial combination of gases.

The divers would live inside a chamber pressurized to that of the dive site -- seventy meters under seawater -- breathing up to ninety percent helium mixed with oxygen for the duration of the operation. This would allow the divers to operate continually underwater, and they would face only one three-day decompression procedure when they finally exited.

In May 1999, the 220-foot Tropical 388 arrived on the scene. The barge was fitted out with a complete saturation diving unit that included a pressurized cabin, a detachable diving bell and a rescue chamber that could be cut free if necessary. For the next seventy days the divers from Australia, New Zealand and Ireland would eat, sleep, read, listen to music, watch TV and most of all work inside the restricted quarters that looked like the interior of a space shuttle, only smaller.

What they could not do was have a little privacy. A crew of nineteen life-support technicians and twelve supervisors kept the divers under round-the-clock video surveillance to ensure their safety and health. The technicians were responsible for monitoring the mixed gas supply and the environment of the living unit, operating the gas reclamation system and ensuring the food supply via an airlock.

The six divers were split into three-man teams. By alternating twelve-hour shifts, which allowed them to jointly work twenty-four hours a day, one team remained in the living quarters while the other descended to the sea floor in the detachable bell. One diver, acting as supervisor, took direction from a topside archaeologist, while two of the divers swam out to the wreck. An "umbilical cord," connecting the bell to the topside unit, channeled everything the divers needed, from gasses to hardwire cables. Hot water was pumped down and circulated in the suits around their bodies to keep them from freezing to death.

All in all the divers' time, not only in the water but inside their living chamber as well, was consumed by the variety of tasks assigned to them. At times they were compared to robots, with the sole reason for their existence to be the eyesight and manpower of the supervising archaeologists.

They took photographs, measured, kept logs, installed steel grids over the entire wreck and methodically handled each individual artifact under direction from the archaeologists on the ship above. "Because of the light sensors on the cameras they used, we could actually see what they were doing better than they could themselves," Bound explains.

So many pieces meant that the crew needed a system that could bring up more than one at a time. The solution was a giant crane situated on the deck of the salvage barge. "The people who stored the ship made everything easy for us by laying it out in a line," says Bound. "We would fill a crate in line with the ship, then use the crane to bring the crate to the surface. There could be as many as 8,000 pieces coming up in a crate at one time."

Bringing the artifacts to the light of day was just the beginning, as far as the entire archaeological excavation process was concerned. Each piece was transferred topside to the Abex and the OL Star, storage and desalination barges, where twelve washers were waiting to clean the pieces as soon as they came up.

After being cleaned, a piece was placed in a desalination tank, to keep it from drying out and cracking. The tanks were laid out according to the grid system that had been laid over the entire wreck site, to keep track of where the artifact had originally been located. In essence, the tanks were a meticulously assembled representation of the shipwreck.

This operation, in conjunction with the dives, involved 120 men, including archaeologists, photographers, artists and technical crew. While these teams labored round the clock on three main barges, they were kept under the watchful eye of the Vietnamese Navy, whose responsibility it was to keep pirates away.

A recent AP article had reported "an alarming jump in the destruction and ransacking of shipwrecks in many Asian countries, including Vietnam." And a "Vietnam News" report had attributed the recent looting of hundreds of artifacts and antiques to "a shortage of security measures [that] pave the way for thieves."

"Whole ships are known to go missing for weeks in the South China Sea," explains Bound. "We had armed contingents on each of our vessels and gunboat protection." Not only was the military present, but twenty-four hour a day security guards were authorized to search all personnel and their carry-on bags.

In the end, pirates, typhoons and hazardous diving conditions could not prevent the operation from being a success. After desalination, the artifacts were sorted and tagged. They were then transferred a warehouse outside Da Nang, where a workforce of over sixty continued cleaning, photographing, drawing and recording, preparing the porcelain for its final destination -- the outside world.

At 65,000 US dollars a day, the final cost of this journey from seabed to history-in-the-making was four million dollars. Is such an escapade worth that much? Historians and scholars would no doubt insist yes. But what about materially?

All unique pieces have been retained by the National History Museum in Hanoi. Another ten percent, selected by type, were dispersed among the more than one-hundred museums throughout the country. Saga received forty percent of all duplicate objects. As for the rest, the collection will be auctioned by San Francisco based Butterfield's. Profits from the auction are to be shared equally between Saga and VISAL, which means that the Vietnamese government is sure to benefit substantially. VISAL is a state-owned company.

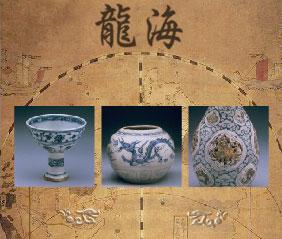

It's difficult to say how much the auction will bring in, since this collection so unprecedented. Many of the designs have Chinese prototypes, but a few are being seen for the first time in history. Butterfield's Asian Art Expert, Henry Kleinhenz, notes the originality of a set of cups shaped like parrots, and the exquisite design of an egg-shaped ewer with a birds head spout. "This is going to be a very unique opportunity for collectors and museums."

"The range was really quite amazing on this ship," says Bound. "You could see the mind of the merchant. You have on one hand, well, not great works of art, and on the other hand these grand magisterial pieces."

While the auctioning of such a collection isn't unusual in and of itself, this situation stands out for two specific reasons. By choosing Butterfield's over the more prestigious Christie's or Sotheby's, the Vietnamese government will be hawking its wares in the US for the very first time. And because Butterfield's is owned by eBay, this collection will the "the first online art sale in history featuring material of this scope, age and importance."

The Hoi An Hoard, as the collection has come to be known, will completely reshape current beliefs about Vietnam's ancient ceramics and trading traditions. Like the country itself, it won't be content to rest on its past laurels. As it is dispersed to collectors around the world, it will carry on Vietnam's tradition of never failing to surprise, and it will remind us once again to not underestimate the talents, skills and ingenuity at work inside this small, Southeast Asian nation.

Learn More About:

Hoi An, Part 2 - The Collection

Hoi An, Part 3 - The Theories

Hoi An Hoard Images

Links to Other Hoi An Hoard Sites

The Hoi An Hoard Auction

(On eBay Great Collections)

The Hoi An Hoard Official Web Site

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian