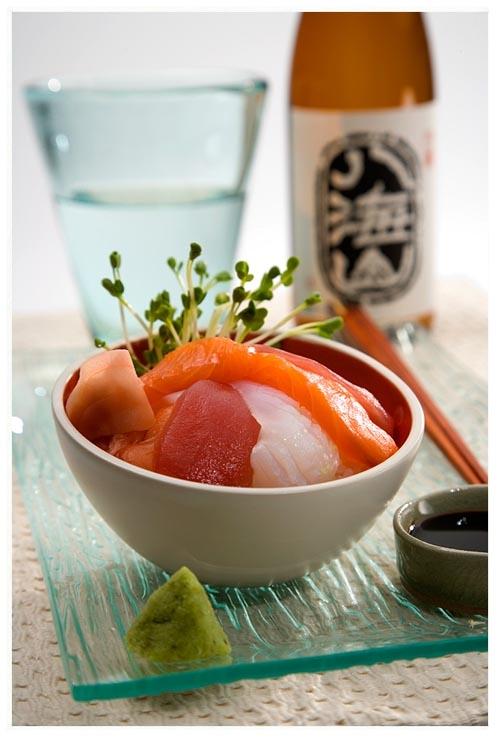

Japan fights to save "real sushi"

Tokyo, December 2006 - From sushi topped with foie gras in France or wrapped around cream cheese in the United States, Japanese food is growing fast and going global. But not everyone in Japan is pleased.

The Japanese government, joined by some leading local chefs, has launched a campaign to preserve "real" Japanese cuisine from a bastardized version that has spread so wildly overseas.

"Our goal is to offer real Japanese cuisine," Agriculture Minister Toshikatsu Matsuoka told a recent conference of food experts in the western culinary capital of Kyoto.

"We don't want restaurants that look Japanese but whose content is nothing but. We would like to differentiate them from those where we can say, Now this is real Japanese cuisine'," he said.

The number of Japanese restaurants abroad will top 50,000 in three years -- twice the current number, according to government forecasts.

The biggest number of fans live in the United States where Japanese cuisine -- which includes sushi, tempura, miso-soup and ramen and udon noodles -- is prized among health-conscious eaters for its low-fat, high-protein ingredients.

It has also enjoyed an explosive welcome in Europe, Russia and Southeast Asian countries where Japanese restaurants have mushroomed in the past decade.

But some Japanese who are travelling overseas are not feeling at home.

Japanese officials and tourists have grown alarmed by dishes overseas that would hardly be seen in Japan, such as long rice instead of the sticky Japonica rice for the sushi.

While Japanese food is often seen in the West as vegetarian-friendly, Japanese tourists overseas have been alarmed by the absence of bonito fish-stock in miso soup.

And not only is the food under fire, but also the service.

"When I went to Paris and entered a restaurant with a sign in Japanese and called to the waitress excuse me, excuse me' in Japanese, she didn't turn around even once," bemoaned Yukiko Omori, a French-style dessert chef.

"It turned out she was Thai. So I don't want there to be so-called Japanese restaurants if they're inconsiderate towards guests and tourists," she added.

For the Japanese government, authenticating food may be a matter of culture -- but it is also good for business.

Some officials hope to solve the dilemma by exporting more Japanese products, particularly "essential" ingredients such as wasabi spice, "nori" seaweed, bonito soup stock and rice-based vinegar.

The Japan External Trade Organization will release a guidebook in January for Parisians listing 50 restaurants in the French capital as real Japanese establishments, out of the 600 that claim to be.

The Japanese government set up a committee of experts on the food authentication issue in November. It is due to reach its conclusions by February.

For purists, the effort is a way to standardize the food and ensure it remains recognizable for Japanese -- unlike, for example, Chinese food which has long taken a different direction in North America to meet local tastes.

"It's about chemistry between ingredients," said Shigeo Nakamura, a leading chef based in the western city of Osaka.

For him, California rolls -- a US variation of vegetarian sushi that replaces fish with avocados or cucumbers -- and cream cheese rolls are simply not sushi.

"Tell me, do you really think avocado and rice go together? They don't go well with each other in the mouth," he puffed.

However, some chefs dismiss the effort as a misplaced cause.

"I don't see what the big fuss is about. Whether you cut sashimi correctly or not doesn't have anything to do with being Japanese but rather on an individual chef's technique," said Sadaharu Nakajima, who worked in Italy and appears on Japanese television.

Some foreign chefs working in Japan have also criticized the initiative as protectionist.

The government "seeks to attract foreign clients in restaurants certified by the government itself, which is an attack on free business," said Stephane Danton, a French restaurant consultant based in Japan.

* * * * *

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian