Psychedelia in Stone: Chinese Temple Architecture

For thousands of years, industrious and ambitious Chinese have left China in search of wealth in other Asian lands. Undoubtedly this Diaspora only accelerated once China fell to the Communists and as its population exceeded all imaginable bounds. Indeed, it could be said that people of Chinese ancestry have been responsible for much of the sudden economic transformation of the so-called Asian tigers: Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and so on.

China's influence on the culture of Asia has been no less pronounced. And nowhere is it more evident - barring the continent's many Chinatowns - than in the countless Chinese temples found beyond the Middle Kingdom, especially in the coastal areas where the sea-borne immigrants often settled, the Thai seaboard among them.

To say that these temples "stand out" from their surroundings would be a gross understatement. "Erupt" is a better word, but still insufficient. The surroundings, in contemporary Thailand anyway, are generally greenery, blue sky, and the dull gray of rain-washed concrete. Against this, the temple presents virtually every color of the rainbow in psychedelic combinations, numerous undulating serpents with fiery eyes and heart-stopping fangs, huge and inscrutable Chinese ideograms.

Though Chinese temples may be even more visually spectacular than Thai temples, they serve much the same, comparatively mundane social purpose: as a place for the community to pray, hold festivals and funerals, park cars, fly kites, make donations, read fortunes, find shade. One temple I visited even seemed to have its own police station and police truck. Some had external gazebos, assembly halls, offices, and all had a sort of hive-shaped, decoratively paneled incinerator.

Like many religions in Asia, Chinese religion tends to be a hodge-podge. As Max Muller wrote in 1868, "It is difficult to say to what religion a man belongs, as the same person may profess two or three. The emperor himself, after sacrificing according to the ritual of Confucius, visits a Tao-sse temple [sic], and afterward bows before an image of Fo in a Buddhist chapel."

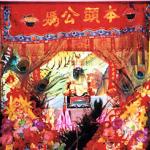

This hybrid nature of Chinese religion is reflected in the articles to be found in a Chinese temple. An inner shrine may contain a few figures of ancient Chinese men (ancestor worship), a garuda figurine (Hinduism), a yin-yang (dualism), and an amulet containing a miniature monk statue (Buddhism). It may also contain a host of other objects whose religious significance is unclear or nil (joss sticks, garlanded elephant statues, tiger paintings, peacock feathers, potted plants.) The result often resembles a stall at a flea market, or a garish and dusty curio store in some Chinatown. (To be fair, I have always bristled at seeing the Stars and Stripes in a Christian church, as if Jesus were a great American patriot.)

One remarkable aspect of Chinese temples is how much of their architectural design consists, simply, of text - predominantly Chinese, but also that of the local language(s). There is writing above, beside, and on doors; on walls; on cloth tapestries and bulbs hanging from the ceiling; on supporting columns. It is almost as if a hymnal had been set in stone.

Text also serves to caption the many illustrated panels on the temples' outer walls. The panels depict different kinds of fruit, animals, and figures apparently drawn from Chinese history and mythology. Here two seated men play Chinese chess while being served tea; there a peculiar pig-headed man holds a farming implement; and over there an old sage, bearing a crooked walking stick, totters down some country road.

Serpents are everywhere. Typically, two serpents face each other on top of the main temple building. Wrapped around the supporting columns before the main entrance are two more. Other columns have lotus filials, with a projecting serpent-head caryatid. Still more serpents project from the temple's inner walls, in one case above a pool illuminated by natural light. In many cases, red light bulbs act as the serpent's sinister eyes.

Colors. Red dominates of course, and gold, but not because these are the flag colors of the People's Republic of China. It is one of those ironies of history that, in China, red traditionally represents good luck or prosperity, but the color was used by the European Communists to symbolize - what? The blood of the proletariat, I suppose, when for the Chinese it had always stood, indirectly, for wealth. This meaning is likely to be the one the temple intends.

Sounds. Like Thai temple compounds, those of Chinese derivation are walled- or gated-in, and the temple itself is set a ways back from the road. Thus, it tends to be fairly quiet. As I was abut to step inside, a flock of small birds darted over my head and into the temple. I could hear them chirping furiously up in the eaves and then realized that they were using for a nest a pair of wicker bulbs dangling from the temple ceiling. Whether this was the bulbs' intended use I can't say, but I was happy to learn that the Chinese, like the Thais, permit animals in their places of worship.

The temple caretakers notice me nosing about, snapping photos, jotting down notes, feeling a bit alien, when a boy runs up to me. He offers me a banana, and when a woman discovers that I speak Thai, she offers tea. With these simple, somewhat disarming acts of generosity they remind me why, though I have tried to leave Asia many times, I never succeed for very long, splendorous Chinese architecture aside.

* * * * *

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian