Through Enemy Lenses: North Vietnamese Photojournalists Shoot the War in Another Vietnam

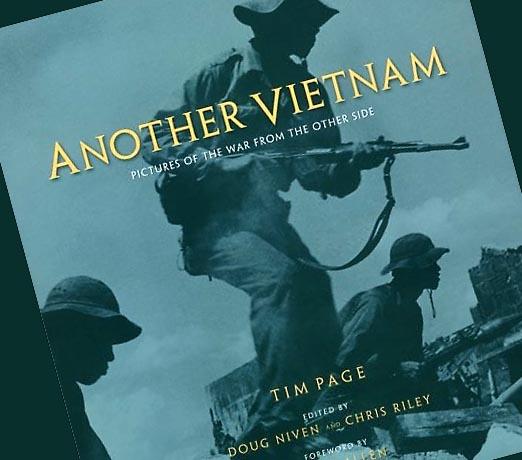

Another Vietnam: Pictures of the War from the Other Side

Tim Page. Edited by Doug Niven and Chris Riley with forward by Henry Allen. National Geographic, 2002. 240 pgs. US$50.00

* * *

American, British and other Western photojournalists covered Vietnam like no war before or since. A small army of photographers literally snapped millions of pictures over the course of that long and bloody conflict. The best of these photos have become part of America’s collective national memory of the war, for no matter what our age or level of interest in Vietnam, we all know the famous pictures that symbolize the war’s exceptional violence—the Buddhist monk burning himself alive, the South Vietnamese police chief shooting a Viet Cong prisoner in the head, the naked girl running in agony from a napalm strike, the desperate escapees boarding a helicopter atop the roof of the U.S. Embassy.

Though these pictures by Western photojournalists capture the war’s brutality with a powerful and unremitting intensity, they nonetheless offer a one-sided perspective of the conflict. What has long been missing from the pictorial narrative of the war is the work of photojournalists shooting from the other side. National Geographic’s Another Vietnam attempts to rectify this imbalance by profiling the combat photojournalism of North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong photographers.

Another Vietnam was the brainchild of photojournalist Doug Niven, who went to Vietnam in the 1990s in search of pictures taken by former NVA and Viet Cong photographers.

“The Vietnamese have a long, rich tradition of arts and literature, so I was sure that a fraternity of former war photographers existed in Vietnam, unknown to us in the West,” Niven writes in the book’s introduction. “I decided that I would try to find those photographers, collect their pictures and record their stories, with the simple goal of adding their images to our memory of the Vietnam War.”

Eight NVA and Viet Cong photographers are featured in this coffee-table book of beautifully reproduced black-and-white photos. Each photographer tells his story—unlike in the Western press, combat photography remained an all-male preserve—in his own unique voice, a story backed by a powerful collection of war photographs.

Chapters by Tim Page, a famed Vietnam War combat photojournalist, are interspersed between chapters devoted to individual NVA and Viet Cong photographers. In language that is informal and slang-laden as well as honest and insightful, Page explains that while Western and NVA/Viet Cong photographers were alike in many ways, they were nonetheless two distinctly different breeds.

Page notes that while Western “shooters” or “snappers” worked for the international media, NVA and Viet Cong photographers worked for the liberation of Vietnam. They owed no allegiance to journalistic objectivity and viewed their photos as weapons in the struggle to free their country. Page writes, “Their mission was to document the nationalistic cause, the heroic, however grim it had become. To prove to themselves and to their fraternal allies that their cause was righteous.”

Thus in Another Vietnam we see many beautifully shot but nonetheless propagandistic photos of handsome NVA soldiers mingling with grateful villagers, north Vietnamese militia women standing guard with bayonets at the ready, and resolute Viet Cong guerrillas with captured M-16s and bare feet.

The book’s well-chosen cover photo is an artfully composed propaganda action shot by Le Minh Truong. In this 1972 photo three NVA soldiers leap over a berm of rubble in Quang Tri, weapons at the ready. Their faces are all in shadow, and this lack of specific identity suggests that their heroic charge represents the courage of all NVA troops.

While many photos serve such obvious propaganda purposes, many others depict the brutal reality of the conflict. Unsurprisingly, there are no photos of NVA corpses, though several poignant portraits depict men and women who went on to die in the war, sometimes just hours after their pictures were taken. As might be expected, there are numerous images of dead, wounded and surrendered South Vietnamese soldiers as well as American POWs.

Surprisingly, however, many of the photos in Another Vietnam display a stark and raw beauty that jars with the war’s death and destruction. A photo by Le Minh Truong, for example, depicts a column of troops moving up a jungle ravine as beams of sunlight shoot through the misty air. Another one of his shots catches a patrol clambering up a peak, a vast panorama of cloud-wreathed mountains in the background.

In an act of improvisational genius typical of NVA and Viet Cong photographers, Van Sac created a wide-format image by carefully pasting together six consecutive photographs. The resulting panorama shows battered trucks moving along a curving portion of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. American defoliants have killed the jungle, and the trucks rumble through an almost gothic landscape of dead tree trunks and barren rock.

In what may soon become a classic photo of the war, Vo Anh Khanh depicts a makeshift operating room in a mangrove swamp on the Ca Mau Peninsula. The nurses and doctor stand in calf-deep water, their only shelter a roof of mosquito netting, as stretcher bearers bring in an unconscious young guerilla for surgery. Even with their masks on, the nurses’ solemn, intense focus comes through; around them is the overgrown beauty of the jungle. Few photos better capture the dedication of the Viet Cong to their cause.

The excellence of the photography in Another Vietnam remains all the more remarkable given that NVA and Viet Cong photographers carried only the most rudimentary photographic equipment. Most carried a single camera body with just one standard 50mm lens. They lacked darkrooms, so they mixed processing chemicals in tea saucers and developed film in the bush on moonless nights. Film remained far more precious than ammunition. Photographer Tram Am took only one 70-shot roll in the entire war. “I didn’t have extra film and didn’t know how to change the roll,” he recalls.

Foreign photographers faced enormous risks while covering the Vietnam War. At least 73 were killed during the conflict, and Tim Page himself survived a near-fatal head wound. However, foreign journalists could calculate the risks and work the odds. If their gut instincts told them a story was too dangerous to cover, they could opt not to do so. Their counterparts in the NVA and Viet Cong, however, had no such choices. They were soldiers under orders to cover the story or die trying, and unlike their Western counterparts, routinely carried weapons along with their cameras.

The NVA and Viet Cong photographers featured in this book all shared a dedication to their work as well as their country, which meant that they never hesitated to cover even the most risky of stories. In one chapter Nguyen Dinh Uu recounts how he was assigned to photograph a battery of 37mm anti-aircraft guns. “I remember the danger as American planes came roaring right at the gunners, who didn’t flinch,” he says. “The gunners stood there and fired at the diving planes, and I stood right behind them shooting pictures.”

In another chapter, Dinh Dang Dinh describes a bombing raid he survived on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. “I had to abandon my equipment and run,” he says. “If I had tried to save my gear, I would have lost my life. But in an instant I lost all my work. It was all destroyed, everything. I even lost my sandals and my hat. All I had left were my shirt and pants. I was lucky to have escaped.”

Many of Dinh’s fellow photographers were not so fortunate, as a large but unknown number died during the war. Their photos are their legacy, a legacy that Another Vietnam handles with respect, sensitivity and insight. No library’s Vietnam War collection will be complete without this important and ground-breaking work.

* * * * *

Available at Amazon.com

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian