The Jeepney: Automotive Icon of the Philippines

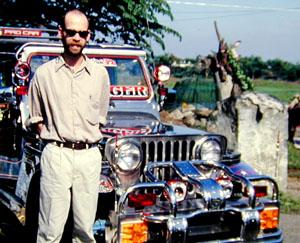

As any world traveler knows, each Asian country offers its own unique brand of public transport. Passengers in Japan, for example, rocket down the tracks aboard sleek 170-mph Bullet Trains. In Vietnam, however, passengers move at a sedate five mph while sitting in cyclo pedicabs. Passengers in Thailand buzz about in three-wheeled tuk-tuks, while in Hong Kong they steam across the harbor on green-and-white Star Ferries. And perhaps most famously of all, the Filipinos cruise along in style aboard chrome-plated jeepneys that literally dazzle the eye.

As is true throughout the world, most forms of Asian conveyance are strictly functional. This remains as true of the ultramodern Bullet Train as the human-powered Hanoi cyclo. But while the jeepney certainly offers a practical means of getting from A to B, it is much more than just a form of public transport. After all, jeepneys embody the history of the Philippines in the 21st century. They also stand as a testament to Filipino mechanical genius. Most uniquely of all, jeepneys are mobile works of art that dominate streetscapes from Luzon to Palawan.

Like an automotive phoenix, the jeepney rose from the ashes of Manila at the end of the Second World War. After Japan's surrender in 1945, the U.S. military began sending millions of American servicemen home to their peacetime lives. Much of their surplus equipment stayed in the Pacific, however. In Manila, which had been leveled when the Americans retook the city street by street from the Japanese, the U.S. Army sold or simply gave away a huge number of surplus jeeps to local Filipinos.

Manila's transportation infrastructure had been destroyed in the fighting, so entrepreneurial Filipinos began using these surplus jeeps as share taxis. Drivers soon began painting their olive-drab jeeps in a bright rainbow of peacetime colors designed to grab the attention of potential passengers. Drivers added metal roofs to ward off the sun and rain; they extended the rear of their vehicles in order to crowd more people aboard. An entire range of accessories followed-chrome hood ornaments, ear-shattering airhorns, religious icons and flashing multicolored lights. Manilenos suddenly realized that an entirely new sort of vehicle had been born in their war-ravaged city.

In creating the jeepney the eclectic Filipinos had taken a quintessentially American item-the Willy's Jeep-and modified it to suit their own needs. This is a common story in the Philippines, which was an American colony for fifty years. During that time the Filipinos acquired a great deal from their colonial masters, including English. As they did with the Willy's Jeep, however, Filipinos took American English and turned it into something all their own. In this sense, the evolution of the jeepney mirrors the history of the Philippines in the 21st century.

Fifty-seven years after the Second World War ended with a double atomic bang, jeepneys are still hauling passengers throughout the Philippines. Though these sturdy machines face increasing competition from more modern sedan and minivan taxis, jeepneys remain the backbone of public transportation. Many jeepneys operate in the Metro Manila area, but a large number also ply jungle back roads as well. Unlike a bus or minivan, a jeepney can handle a muddy country track with ease.

Today's jeepney drivers face an ever-increasing amount of rules and regulations. Most residents of Manila agree that this is largely for the best. An anti-noise ordinance, for example, now forbids Metro Manila jeepney drivers from cranking up their high-decibel stereo systems. A government agency issues licenses for jeepney drivers to ply established routes at set fares that begin at a very reasonable 2.50 pesos (five U.S. cents). A jeepney driver who picks up passengers off his licensed route faces stiff penalties as well as the potentially violent ire of the drivers whose fares he is poaching.

Nonetheless there is still an outlaw feel to the jeepney, a vehicle that is irrepressibly exuberant in its chrome finery. For all the attempts to bridle them with government regulations, jeepneys still lack safety gear as basic as seatbelts. Ride in a radio taxi and you will simply go from one place to another in seat-belted comfort; ride in a jeepney and you will enjoy a uniquely authentic Filipino experience, complete with passenger camaraderie, hard bench seats and the occasional white-knuckle road maneuver.

You will also be riding in a custom-built example of Filipino mechanical genius. Throughout Asia the Filipinos are famous for their musical talent, but they are hardly renowned for their automotive flair. Nonetheless they rank among Asia's most talented grease monkeys, a predilection likely picked up during all those years as a colony of the car-loving United States.

The original jeepneys were modifications of existing military vehicles. However, since the U.S. military has long since run out of surplus jeeps to give away, today's jeepneys are quite literally manufactured from scratch. As might be expected, they aren't rolling off the high-tech assembly lines of Toyota and Ford. Instead, independently owned factories turn out homemade jeepneys tailor-made for aspiring drivers.

One such factory is Hayag Motorworks outside Manila. Owned and operated by a former jeepney driver named Pedro Hayag, the factory manufactures up to fifty vehicles a month. Mr. Hayag employs a corps of skilled mechanics who can assemble a jeepney from a used Isuzu engine, a reconditioned Toyota transmission, a set of retreads, a tangle of rusty steel bars and a pile of sheet metal. They use low-tech tools like handheld welding torches and ballpeen hammers. The whole process takes up to two months, but the end result-a gleaming chrome masterpiece-is well worth the time spent.

After all, the workers at Hayag Motorworks labor like inspired artisans to produce rolling works of art built to catch the eye. No two of their flashy machines are ever alike, which explains why they all have individual names painted above their windshields. Flamboyant overkill characterizes these jeepneys, which sport not one but four silvery hood ornaments-usually galloping horses-along with chrome pushbars, rows of mirrors, ranks of radio aerials and an uncountable number of reflectors. Many have elaborate paint jobs; others are decked out in a mirror-bright chrome finish. Deluxe models feature onboard color TVs and air-conditioning, not to mention power steering and four-wheel drive.

Unsurprisingly, a new jeepney does not come cheap by local standards. A basic model goes for about 250,000 pesos ($5,000), while a deluxe version fetches as much as 400,000 pesos ($8,000). The jeepney market remains robust, however, as evidenced by the many dealerships set up along the road from Manila to Cavite.

Asian public transport tends to mirror the country it serves. The Bullet Train suits Japan, a futuristic country operating with hyper-efficiency. Hair-raising rides in Thai tuk-tuks are par for the course in the traffic chaos of Bangkok. And the slow Vietnamese cyclo blends into the narrow lanes of Hanoi's historic old quarter. Likewise, the jeepney mirrors the Philippines, a nation that is American influenced as well as boisterous, colorful, pragmatic and chaotic. No vehicle could offer the Filipinos a better ride.

* * * * *

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian