Ancestors

A thin glaze of steely clouds frosts the sky. Leaves, like shriveled claws, scratch along the pavement. It rains less and later in the afternoons these days, and the nights are relatively cool.

But inside a stacked, three-story house in District One, the morning is growing uncomfortably hot. The district is experiencing one of Saigon's many power outages. The fans have wound down into a state of inertia.

Tuan lifts himself from the creaking, low-slung folding chair in which he sleeps. As Tuan has no sons, he believes it necessary to stand guard every night, parked just behind the metal accordion-style front doors. He has three daughters and they are all beautiful.

Tuan folds his chair and stows it against the wall. He walks through the dark front room, the dark dining room and up the dark stairs to the dark living room. He turns on the stereo. He plays an old cassette as loud as he can, ensuring that his daughters do not roll toward the walls, pulling their pillows over their heads, ignoring him as they sometimes do.

Today they cannot begin late. Today is the fifty-fifth anniversary of Tuan's father's death.

In Buddhist families, the responsibility of tending the spirits of ancestors belongs to the eldest son. Each year, Tuan's brother officiates over the memorial ceremonies in his home in one of the southern provinces. Usually, if a younger sibling lives in a distant area and cannot attend, he arranges a smaller ceremony of his own. Tuan's wife, Mai, is Catholic. When they were married, Tuan agreed to give up his role in this practice. He had been faithful to his promise...until this year.

Not long ago, Tuan had this dream: He was driving his motorcycle through the city when he saw an old hunched figure in impoverished clothing shuffling down the busy sidewalk. He slowed beside her--the woman was his mother. "What are you doing here?" he asked her. She replied, "I am tired. I am cold. I am hungry. I am looking for you. Your father and I want to come live with you." Tuan helped his mother onto the back of his Honda and brought her home and gave her over to Mai's care. Mai bathed her in hot water and dressed her in new clothes.

When Tuan woke from this dream, he was weeping.

Many Buddhists, whether practicing or lapsed, are influenced by the religion's strong regard for family loyalty. It is unlike the West where children often lose interest in their elders before they've greyed, let alone concern themselves with their afterlives.

Tuan sat for many days following his dream, pondering the possibility of his parents wandering, their souls fragmented, their old bodies not entirely at rest. Finally, he told his daughters. Lien, his empathetic middle daughter, approached her mother. She said, "Father wants grandmother and grandfather to come and live with us. Please let him do this." Mai consented.

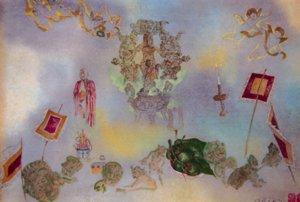

Tuan began constructing an altar. It was a simple, unobtrusive box that stood upright to support the formal black and white photographs of his parents in their youth. His mother wore a simple silk gown and his father wore a traditional ao dai. Beneath the box was a small platform on which to place the daily offerings of incense and tea. Tuan arranged everything in the dining room, out of the way, in a back corner underneath the stairs.

Tuan's daughters are strict Catholics--they believe in Jesus and Mother Mary. On Sundays, they kneel in the Gothic Cathedral on Hai Ba Trung Street. But, they are also Vietnamese: they know how to adapt. They easily accepted their new duties of caretaking the souls of their grandparents through the medium of the two stoic figures in the faded portrait. Everyday they light the sticks of incense that look like slender pussywillows and smell of dark, haunted temple shadows. They whisper prayers inviting their grandparents to join the family while they eat. When asked if she finds this contradictory, Lien says simply "My grandparents are Buddhist." On this morning, the sisters rise quickly to help their father prepare.

If Tuan had been the oldest son, he would have begun the main ceremony on the eve of the anniversary. He would have hosted dinner, inviting relatives and close friends. On the actual day, he would have provided another lunch and dinner. A secondary ceremony, although important in its own right, is not so elaborate.

Tuan is a small man and he has to rock the dining table into position at the base of the altar. His father's favorite cakes have been purchased and Tuan stacks the pink and green snowballs, made of rice flour and bean paste, in the shadow of his father's photograph. He fills the thimble-sized cups with tea and alcohol. On the end of the table, he fans the paper clothing and paper money that will contribute to his father's comfort in the afterlife.

Guests arrive. They offer apples, grapes and lychee fruit. Because of the power outage, miniature oil lamps hem the table. Although the air in the dining room is still, the small wicks incline toward the photograph, as if drawn by the steady inhalation of the dead man's breath. After the guests pay their brief respects, they depart.

It is nearing time for lunch. On a death anniversary, no one in the house is allowed to eat until the honored relative's needs have been provided for the upcoming year. Tuan lights the incense and stands before the table. He prays while his father eats. The two men, one a spirit, the other aging flesh--his own mortality faint but indelible in the back of his mind--commune for the length of time it takes a stick of incense to burn down and out, rushing a coil of earthy smoke into the room.

Meanwhile, the sisters squat on a circle of low wooden stools in the kitchen. The kitchen is twice as large as any other room in the house and filled with more dented pots, dull knives, faded plastic spice containers, blue ceramic pottery, dogs and cookstoves than any family of five could possibly need. It is the sort of place that daily industry and accumulation have made into a shrine of its own.

The sisters bend over flat metal discs stacked with layers of rice paper and enormous plastic bowls that are filled with glistening "salads" as basil and lettuce and other such greens are called in Vietnam. With a dexterity inherited from observing the skills of their mother and the family maid, they add to a growing pyramid of spring rolls. Some of the spring rolls are for lunch; most will be distributed as a form of thank you for the offerings from the morning guests. "We don't eat meat today--my grandparents were Buddhist," Lien explains, once again with a practical acceptance that discourages further inquiry.

Each of the sisters takes a turn murmuring her own private prayer. She stands humbly at the foot of the table and requests her grandfather's blessings and protection for the year to come. She presses one end of the smoldering incense between her flattened palms and bobs her upper body three times, the supplicating gesture a fundamental part of this ritual.

The two sisters who are not praying help clear the kitchen in order to make room for a knee-high ceramic urn. Tuan carries in a small table which he places within arm's reach of the urn. He transfers the paper clothing and the money from the dining table. With little pomp, Tuan unfolds a paper shirt, touches a match to its hem and holds it until the flame usurps the paper. Then he flicks it into the urn.

In the markets and on certain streets (particularly in the predominantly Chinese district of Cholon), there are stalls and shops that specialize in everything that might be needed for a ceremony such as this. They sell candles and incense as well as altars themselves--ready-made, hot pink, studded with pinwheels of flashing lights. It was in one such market that the family maid purchased the brown tunic and matching trousers for Tuan's mother and a mandarin-style blue suit for his father.

The purpose of this clothing is to ensure that the couple does not get too cold or look too shabby in the afterworld--like all worlds, it seems to be a place where maintaining appearances is paramount. So that there will be no question as to where the clothing comes from or where it is supposed to go, Tuan's parents' names and Tuan's and Mai's names have been written on each article.

One-quarter of the kitchen ceiling can be rolled away for ventilation purposes in the dry season. It is drawn back today as the power outage has eliminated the necessary circulation by fans. The air reeks of the rich, musty, sour odor that accompanies the burning of damp autumn leaves. Dark hair clings to moist foreheads. Lien swats at the smoke with a paper fan.

Tuan jabs the fire with a metal poker, making sure that the shoes are burned properly. The shoes, hard cardboard husks, are the most difficult to burn. He finds an offender, a half-charred slipper, and attacks it, beating it back into the flames. Cinders the size of swifts flock overhead. No one ducks. No one seems to notice the possible danger of catching on fire.

Lien continues her fanning and points at a large ash spiraling upward in a vortex of hot air. She says, "Each ash that rises out of the urn means grandfather has received one of our gifts." Tuan's gleaming skin mirrors the coppery tremble of the flames. He takes a balled handkerchief from his pocket and wipes his face. He motions to his eldest daughter, Nga, and passes the poker as if passing the torch, which, in a way, is the case. Because Tuan has no sons, Nga often plays the roles of both son and daughter in family ceremonies.

Nga's prodding is even more lunatic, more zealous, more negligent than her father's. Fire encircles the urn and washes away from it like a wave across the floor. Nga jumps back, although less than an inch. She laughs, "I am not a professional." The family housemaid is a devout Buddhist. She kneels over the urn and bravely plunges in one hand. In order for the ceremony to succeed, there should be no stray sleeves or collars left unburned.

Finally the clothes are incinerated to everyone's satisfaction. Thuy, the youngest daughter, stands beside Nga and slowly deals out the bundles of paper money. Just as there are hunger pangs and cold weather in life after death, there is also the problem of finances. Living a comfortable life, even for someone who is dead, does not come cheap. For basic necessities, a lampoon of the local currency is offered. For unpredictable expenses, there is Hell Money.

Lien says, "We do not know where he is--we have to take precautions. Thuy holds out a stack of Hell Money for closer inspection. She draws attention to the black, boldly printed "United States Dollar," and looks up with a sly grin. Nga explains, "You need a strong currency in hell. And what if you want to travel? Dollars are easier to exchange."

She takes the bundle from Thuy and lowers it into the urn. The money ignites, but the flames do not howl in anguish or lick the sky. This is a bit of a letdown considering the place for which it was destined. Instead, the Hell Money joins the heap of smoldering ash and Mai announces that it is finally time for the rest of the family to have lunch.

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian