Pirates of the East

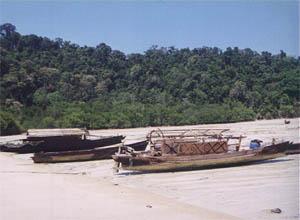

On the Thai islands north of Langkawi, along the exotic islands around the Andaman Sea, small black men perch on the rocks fishing with lengths of twine. Scattered along the shoreline are their villages: small huts with fish traps lying around them, trays of gamat (a type of grass) drying over smoking fires and traditional Malay boats pulled up onto the sand. These people are the last direct descendants of the Orang Laut or sea gypsies.

In Malaysia they have long since married into the Malay community and their language, culture and identity have been lost to the extent that we are in danger of forgetting what a central role they played in our early history. Originally from the Spice Islands in Indonesia, the Orang Laut have migrated all the way here after ceasing their original role as pirates of the Straits of Malacca. The Malays of Southern Thailand still know the Orang Laut well.

"They are black because they spend all day in the sun," an old fisherman told me. "Their language is just like Malay, but they have words from every other language. In 20 words one will be Malay, one Chinese, one Indian, one Arab... they are always moving, and always mixing with sailors."

These days the Orang Laut restrict their activities to fishing and collecting gamat, a sea animal used to produce medicinal oil, coral, sea cucumber, and other products of the sea.

Five hundred years ago, however, they roamed the Straits of Malacca in bands, raiding, burning and pillaging. And, whoever controlled the Orang Laut, controlled the seas. They are the old pirates of South East Asia, not as well-known as their counterparts in other parts of the world perhaps, but certainly a group that influenced the political scenario and history of Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and Philippines.

In 1511, the Portuguese gained control of the land of abundance, Malacca. The Sultan of Malacca had fled with his family to Johor, and Malacca lay in ruins, to be rebuilt and fortified by the European conquerors.

To the Malays, the protection of the Sultan's line was all-important as he was the last direct link with the ancient kings of Malaya. He embodied the mythical descent from Alexander the Great, and Sri Tri Buana, one of the three princes who appeared miraculously on the sacred hill of Bukit Si Guntang in southern Sumatra.

So, the Orang Laut took it upon themselves to protect the Sultan and the Malacca royal family. The Sultan's Orang Laut retainers took him to the east coast of Sumatra where he died, and the powerful magic and prestige of the Malaya line passed from the Sultanate of Malacca to the kingdom of Johor when his son Sultan Alauddin Riayat Syah married into the royal family of Pahang and built his palace at Pekan Tua on the Johor River in the early 1530s.

Sultan Alauddin's task was to win back the influence that his family had lost to the Portuguese in Malacca by establishing Johor as a trading centre. He made little progress at first. Half his energies had gone into building a new State and what remained was not sufficient to hold off his two powerful and well-established enemies.

The Portuguese had the advantage of European ships and firearms, and secure lines of communications stretching to India, Africa, and back to Portugal. The Achenese were based closer, and had centuries of experience of fighting and pillaging behind them.

Against them Sultan Alauddin had only one strong card in his hand. The Orang Laut pirates who controlled shipping in the Straits of Malacca and the waters around Singapore were loyal to the descendants of the Malaya line.

Despite their pirate allies, the Sultans of Johor suffered a series of crushing raids and defeats at the hands of the Portuguese and Achenese. All efforts to establish Johor as a major centre of trade appeared to be in vain until the Sultans received help from an unexpected quarter.

In the late 16th century the Dutch appeared on the scene and it became immediately apparent that Johor and the Dutch were natural allies. The VOC, or Dutch East India Company, had as little love for the Portuguese as the Sultans, and Acheh was just another troublesome competitor.

The tide turned in 1636 when Sultan Iskandar Muda, the warlike ruler of Acheh died, and the Dutch approached the Sultan of Johor over plans to turn the Portuguese out of Malacca. The Sultan decided to throw his lot in with the Dutch and when Malacca was besieged in August 1640, it was the Johor Malays who dug trenches, built blockades and supplied the Dutch with food. The Portuguese held out for five months, and their resistance finally collapsed in January 1641.

As a reward the Dutch signed a treaty of peace and mutual friendship with the Johor Malays, which granted them special trading rights and a guarantee to protect them against Acheh. However, with the support of the Orang Laut, the Sultans of Johor were more than a match for the Dutch. They immediately began to establish Johor as a major trading centre. Because the Asian traders much preferred to do business with each other than with the Europeans, the variety of goods available in Johor was soon much greater than in Malacca, and the prices were cheaper. The Dutch merchants complained to the VOC headquarters in Batavia (Jakarta) and begged them to destroy Johor.

It was time for the Sultans to play the Orang Laut card. If the VOC honored their alliance, the Orang Laut would continue to protect Dutch shipping. Should an expedition be sent against Johor, the Sultans would unleash the Malay pirates, and an immense disruption of trade would ensue.

The VOC took the sensible course, and left Malacca to its new role of protecting shipping in the straits. Until today Johor is a prosperous trading centre while Malacca remains a commercial backwater.

The Orang Laut were so important to the Malays and so respected by them that gradually the two communities fused into one. Malay men married Orang Laut girls; one by one the Orang Laut converted to Islam and adopted the Malay language and customs. In fact, some royal families in Malaysia have Orang Laut ancestors!

Those who retained their old way of nomadic life moved on to South Thailand where many still working as fishermen and remain one of the poorest minority groups of Asia. Education and economic status of this group remain at the lowest level. It is evident that those who did not assimilate into the Malay way of life have somewhat been a forgotten breed.

I suppose it is fortunate that the descendants of the sea gypsies continue to carry this intriguing chapter of Malaysia's history with them as they sail the Thai waters of the Andaman Sea. However, theirs remain one of the few dying sea gypsies population in South East Asia. Showcasing their unique heritage would enhance the lifestyle of these people. Another dying breed of sea gypsies relying on the Andaman Sea for their livelihood are the Moken people. More about them is the next article!

Visitors can visit exotic sea gypsy villages around the Andaman Sea in Thailand. The Orang Laut live around the islands and shores between the Malaysian border and Phuket in Thailand.

* * * * *

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian