Soul, Searching

It was at the glorious Powell's bookstore in Portland, Oregon that I saw Pico Iyer speak. He was on a tour promoting his book The Global Soul, and I suppose it is appropriate that he swept into the room as if his plane had just landed on Burnside Avenue. He rather looked like he was suffering (as we all seem to nowadays) from an overdose of caffeine. Or maybe it was just stage fright. Iyer, who spends part of every year in a monastery, also lives in rural Japan, where, as a man of Indian ancestry with a "longsuffering" Japanese girlfriend, he is virtually anonymous. But Iyer's jitters that day seemed to be an essential source of his eloquence, no doubt also a product of his having been educated in some of the best schools in the world: Eton, Oxford, Harvard.

I don't remember much of what he said, but I will always remember how summarily he dispelled any illusions that writing is an easy or otherwise enviable job; and in The Global Soul he says that he became a writer in part because his estimable education left him with little incentive to do anything else. And while prophets of globalization have become a dime-a-dozen these days -- with everyone from Thomas Friedman to Benjamin Barber framing the world in terms of Lexuses, olive trees, McDonald's and mujahedin -- Iyer is inarguably the most fun to read.

The Global Soul is Iyer's term for people much like himself (and much like myself), people for whom questions like "Where are you from?" or "Where is your home?" have no simple answers. Migrants, refugees, dual citizens, jet-setters, expatriates, "half-breeds" and their parents -- all qualify in some sense as global souls, and they represent, barring any unforeseen catastrophe, the future of humanity whether we like it or not. Like Barber, Iyer sees the world as simultaneously integrating and Balkanizing, a vertiginous world in which it is sometimes impossible to tell whether you are in Hong Kong or New York. It is a world that, as Conrad wrote in Victory, sometimes resembles "a garish, unrestful hotel."

Or an airport: Iyer devotes a chapter to his musings on LAX, where he purportedly decided to live for some time, and which he sees as perhaps the ideal symbol of the globalized world. Possessing virtually all of the characteristics of a city -- churches, a post office with its own zip code, a police force -- it lacks one critical element: residents. And as Los Angeles has one of the biggest foreign-born populations in the world, LAX is both microcosm and gateway, the Ellis Island of our day.

And if LAX represents the world as airport, Hong Kong is the world as hotel and shopping mall, a city where (as Han Suyin put it in her novel A Many-Splendored Thing) you can buy anything. There Iyer introduces us to a friend of his, a management consultant who travels so much that he has several phone numbers, residences, bank accounts. He even has two passports because they fill up so quickly with stamps. One is tempted to pity this man more than anything, as a kind of plaything of capital unleashed, rather than hold him up as a postmodern hero. I know a man like him, and he is not a happy man. Wealthy and well-traveled, but not happy.

And neither is an Indian friend of Iyer's, a friend whose main problem is that he considers himself more English than the English, who supposedly have exchanged fair play and decency for dollars and football jerseys, and whose favorite food is now Indian curry. The Indianization (and indeed Islamization) of John Bull may be regrettable but it was basically inevitable, as colonial subjects took up Macaulay's proposition and became English in everything but their ethnicity. And nowadays the best writers in the British tradition are all from former colonies: Arundhati Roy, Salman Rushdie, V.S. Naipaul.

And Rohinton Mistry, the Bombay-born Canadian whose novels Iyer has elsewhere compared to those of Thomas Hardy, and whom he considers the best Indian novelist writing today. Mistry's name comes up when Iyer is in Toronto, as does that city's own Michael Ondaatje, the Sri Lanka-born author whose novel The English Patient is populated by what Iyer calls "postnational" characters. Toronto itself is trying to be postnational, and Iyer enticingly compares it to Paris in the twenties, a magnet for creative and eccentric people from all over the world.

In another chapter Iyer takes in the Olympics in horrible Atlanta, which for all its significance for globalization (CNN, Delta Airlines, and Coca-Cola are all headquartered there), remains a fairly provincial Southern city, while the Olympics present the contradiction of a world united by the ferocity of its nationalisms.

And last but not least is Japan, where Iyer feels most at home precisely because Japanese society is so structured and exclusive -- where he can be the perfect stranger that he is. Frankly, his village just outside of Kyoto seems frightfully dull, but then I suppose if I traveled as much as Iyer does, dull would be fine. Of the Japanese Iyer makes the excellent observation that though of all Asians they are probably the most eager to adopt and imitate Western things, they somehow manage always to put a Japanese twist on them. Unlike so many other writers concerned with Asia, Iyer does not seem particularly afraid that it will be steamrolled by the West, and in this I think he is correct. More likely is that the East/West distinction, already a problematic one, will simply fade away. Things are changing more rapidly now than they ever have, but it is simply ridiculous to believe that millennia-old institutions will suddenly gasp their last and die. It's a sobering thought, for example, that the number of adherents to Islam, conceived about thirteen centuries ago, is growing -- in traditionally free-thinking England, no less. For every action, said Newton...

Much of Iyer's book is taken up by cultural juxtapositions that have become as commonplace as they should be astonishing. So, he writes, "I hardly notice I'm sitting in a Parisian cafi just outside of Chinatown (in San Francisco), talking to a Mexican-American friend about biculturalism while a Haitian woman stops off to congratulate him on a piece he's just delivered on TV on St. Patrick's Day." Or that Iyer himself has a South Indian surname, an Italian first name, a British passport; Japanese immigrations officials routinely suspect him of being a drug trafficker; he is often mistaken as a person from the Middle East, while Indians address him in Hindi (he speaks none.) I'm sitting in a restaurant in Chiang Mai that is run by Thais but which serves Swedish food and the best pizza in town. Maybe if I get bored of writing I will call my half-Japanese, half-American friend (on my German cell phone), ask him to drink a Danish beer and then ride around on my Thai motorbike whose instrumentation comes from Italy. Or perhaps I'll go to the Irish Pub and chat with Burmese flower vendors, or just go home and watch Korean TV dramas dubbed into Thai.

Another idea that has stuck with me from Iyer's talk at Powell's was what he called "making one's peace with modernity", which Iyer, whose favorite writers tellingly include Emerson and Graham Greene, does in various ways. For a sometime contributor to Time magazine, which has now come to resemble a consumer electronics catalogue, Iyer is remarkably disconnected. For him the purchase of an electric typewriter is a significant act, and he relies on his local, forlorn post office for communication with the outside world. His adherence to these anachronisms puts him in league with, say, Wendell Berry, as an acute observer of globalization who doesn't really participate in it, or does so only grudgingly.

So in a sense it was apt that I saw Iyer speak in Portland, where Intel and Nike, both (sometimes notoriously) global institutions jostle with ragged anarchists and Fight Clubbers, viewing modernity as something with which to make, not peace, but war. Iyer's attitude strikes me as more reasonable than that of both the cheerleaders and the hecklers, and when he describes his daily walks in Japan, I am reminded of Max Ehrmann's advice that we "go placidly amid the noise and haste, and remember what peace there may be in silence."

* * * * *

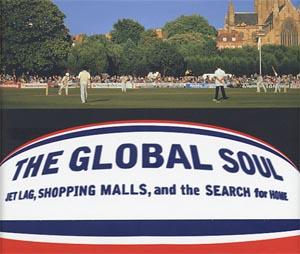

Review of Pico Iyer's The Global Soul: Jet-Lag, Shopping Malls and the Search for Home, Bloomsbury, 2001.

* * * * *

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian