The Himalayan Yeti

The ultimate Himalayan quest after the conquest of Everest? Many have tracked it on the slopes of Everest, but few have seen it. Nonetheless, the mystery of the Yeti has outlived the conquest of the world's highest summit 50 years ago and perhaps represents the last true Himalayan quest.

Tracks in the snow, rare photos -- often fuzzy -- excretions, hairs and disputed testimonies are some of the elements that continue to fuel debate on the "abominable snowman". Half man, half monkey, it is said to live high up in the thick forests of Nepal and Tibet, where it is known locally by the name "migou."

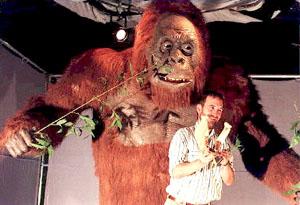

Legends abound among the Sherpas, the ethnic group in the Himalayan valleys, of a mysterious creature, venerated and feared, which moves upright like a man, but bent, endowed with sufficient strength to "kill a yak with its fist," with a pointed head and a body covered in black or reddish-brown hair.

And since the last century, curious westerners have put themselves on the track of the Yeti. Among the most famous are Italian mountaineer Reinhold Messner and, especially, Edmund Hillary, who first conquered Everest on May 29, 1953. Some years after, in 1960, the New Zealander took part in a ten-month expedition to attempt to prove the existence of the Yeti in the Khumbu Valley, to the south of Everest.

But it was in vain. The most convincing evidence was a scalp brought back from a monastery in Khumjung. "My father travelled with Hillary all over the world with the yeti scalp," said Ang Tshering Sherpa, president of the Nepal Mountaineering Association. But scientific analysis proved it was a forgery, made with a piece of a Serow Himalayan goat.

But like other Sherpas of his age, Ang Tshering, 49, still has his suspicions. "There are some mysterious animals left up in the mountain. Nobody knows exactly what these animals are," he says, pointing out stories of killed yaks. Scientists say that in theory, a wild creature could escape the clutches of men in the immense, uninhabited and largely unexplored Himalayan heights.

A relatively recent account comes from American mountaineer, Craig Calonica, who said he saw the yeti in 1998 on the Chinese side of Everest. "It walked like a human, except that it had thick black fur, was about six feet (two metres) tall and had hunched over shoulders with very long arms and extremely large hands," he said.

Various theories have sprung up from accounts like these: a large langur or gibbon type of monkey, a wild man or a rare species of bear. Specialists lean towards the last hypothesis.

"It is not an anthropoid, not a strange creature. This is a high-altitude bear, the blue bear," whose fur looks blue in the sunlight, said Harka Gurung, a former Nepalese minister of education and later tourism and an Himalayan geographical specialist.

The author of many studies and a former advisor of international organisations, Gurung thinks the Yeti exists only in popular belief. On the other hand, the blue bear is rare, lives in the wild forests and can climb to an altitude of 6,500 metres (21,500 feet) in search of food. An omnivore, it can kill yaks if it is hungry, he explained.

"The Yeti is a myth. It's like the Loch Ness monster in Scotland," he said. Even the younger generation of Sherpas are sceptical, adds Commander Bed Upreti, pilot and author of a book on Everest, who himself went in search of the Yeti in 1997 and 2001.

"The Sherpas said: dont waste your time. They say it is easier to climb Everest than to go on a Yeti expedition." He, however, likes to believe in the Yeti, as does Ang Tshering, the president of Nepal Mountaineering Association. "If I took a photo of the Yeti, I would be a very rich man," he said, adding there were always people in search of the mysterious creature.

* * * * *

Fact File

Professor Chris Stringer

The Mythical Yeti

* * * * *

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian