Fan Tan Memories - Victoria's Chinatown

Located on Vancouver Island, the provincial capital of Victoria is the site of Canada's oldest, and the most populous Chinatown until 1910 when it was surpassed by Vancouver. At the time of the building of Victoria's historic Parliament Buildings and The Empress Hotel, Chinatown was a thriving community of 3500 that encompassed six blocks.

The port of Victoria was the first settlement for Chinese immigrants enticed by dreams of a fortune in the Fraser River gold rush or contracted as laborers for the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway. As was the case in Vancouver, racial resentment contributed to the formation of a separate community on the northern fringes of the city.

Unlike the vivacity of its Vancouver counterpart, Victoria's Chinatown is serene, the halcyon days long past. What remains of the once vibrant community is a short strip along Fisgard Street between Government and Store Streets. There are a few restaurants and two grocery stores left, but little of the liveliness and energy that are characteristic of other Chinatowns.

Perhaps the best remaining example of Chinese architecture is the well restored Chinese School Building; built in 1907, the structure has distinctive red tiled, three tiered, pagoda style roofs with up swooping corners and typical recessed balcony.

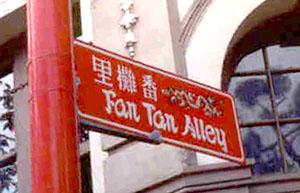

Fan Tan Alley, which in places is as narrow as four feet, runs between Fisgard Street and Pandora Avenue, a distance of over two hundred feet. Once the main entrance to a maze of convoluted passageways and secret escape routes, courtyards, opium dens, and gambling clubs, Fan Tan Alley takes its name from a popular wagering game of the time. Often called "The Forbidden City", this inner sanctum was exclusively for Chinese and was both refuge and enclave.

Cemented in doorways are the only hint of the labyrinth that existed here a hundred years ago; the walls of this once bustling alleyway are graffiti covered and lined with small stores selling candles, wicker ware, artwork and there is even a barber shop. Once teeming with activities both legal and illicit, the air floating with wisps of lingering opium smoke, the alley is now quiet and frequently empty.

Built as part of an attempted rejuvenation of the long declining area in 1981, the elaborate Gates of Harmonious Interest spans Fisgard Street on the west side of Government Street. The red and gold structure is embellished with an intricately carved dragon motif; on either side, there are two protective lions sculpted in China. The gate stands as a monument preserving the memory of a period that is now long past.

The colorful archway was also built as a symbol of the harmony that now exists between eastern and western cultures. It provides a subtle reminder of a time when relations were characterized by resentment, discrimination, and animosity.

As the Chinese population grew, widespread unemployment created hostility towards the immigrants who were perceived as competition for scarce jobs.

After the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1885, and continuing until 1904, the Canadian government levied a head tax on Chinese immigrants that rose over the years from $50 to $500. The tax did not curtail immigration, but did succeed in separating fathers and husbands, who were desperate for prosperity, from their families.

The Canadian government halted further immigration with The Exclusion Act of 1923. As a result, Victoria's Chinatown began its decline. Ironically, it took World War II, when China was an ally and fought with Canada, to bring the repeal of the act. By then it was too late for Victoria's Chinatown.

The discrimination which prompted the formation of Chinatown was not limited only to the living. Chinese buried in The Ross Bay Cemetery, which opened in 1873, were segregated into a section near the sea and given nameless grave markers; since the area was at sea level, graves were frequently washed away during storms.

In 1903, the influential Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association established an exclusively Chinese cemetery at Harling Point, a site selected because of its very favorable feng shui. The graveyard was in use until 1950, and was designated a national historical site in 1996. A recent refurbishing of the cemetery included the construction of new fencing and explanatory plaques.

Although the open-air altar still stands, the "bone house" has been demolished. Until the third decade of the twentieth century, it was the custom to exhume the bodies of Chinese who died in Canada after they had been interred for seven years. The bones were cleaned and stored until they could be shipped to their home villages to be buried with their ancestors. Bones that had been in storage when the practice was discontinued are buried in mass graves marked by large new-looking granite markers, which contrast with the four hundred or so weather-worn, cracked and broken gravestones half hidden by long grass, weeds, and wild flowers.

Like the sealed doors along Fan Tan Alley, the tombstones at Harling point provide mute reminders of Victoria's status as the cradle of Chinese culture in Canada.

* * * * *

Fact File:

One legacy that still flourishes in Victoria is the Chinese penchant for good food. We enjoyed a memorable meal at the Ooh La La Hot Pot Restaurant, which is co-owned by Lin Cai and Brian French and features a style of cuisine originating in northern China. The comfortable booths feature granite table tops that were quarried in Inner Mongolia and custom fabricated in Beijing.

A house specialty is La Mian noodles that are tossed, twirled, and pulled before diners' eyes by either Xue Jian Yan or Bing Cai, the chefs who learned the skill in northern China.

"The noodles are a symbol of longevity to the Chinese," Brian French explained, "but long noodles are difficult to manipulate, especially with chop sticks. We cut them shorter for non-Asians."

We began with a selection of succulent dumplings that are made in either meat combined with vegetables or strictly vegetarian styles. The hot pot broth can be either chicken or vegetarian stock, or a divided container of both can be inserted into the recessed cooking well. Thinly sliced lamb and marbled strip loin, a seafood medley of scallops, prawns, and salmon slices, and a mixed vegetable platter of carrots, lettuce, broccoli, mushrooms, spinach, and baby Bok Choi made up our hot pot choices. At Brian's suggestion, we added the ingredients gradually to prevent over cooking. A plate of La Mian noodles completed our exotic and leisurely hot pot dining experience. "Save some room for the broth, Brian urged. In spite of having eaten far too much, we found the soup to be rich and flavorful, having borrowed from each of the numerous ingredients.

The Ooh-La-La Hot Pot Restaurant

1063 Ford Street

(250) 978.1920

The Chateau Victoria Hotel

740 Burdett Street

Victoria, British Columbia

V8W 1B2 Canada

Phone: 250.382.4221

Fax: 250.380.1950

Web site: chateauvictoria.com

The Chateau Victoria, a Four Star Award Hotel, is in the heart of downtown Victoria and a short walk from the inner harbor and many attractions.

Tourism Victoria:

812 Wharf Street,

Victoria, British Columbia,

Canada V8W 1B2

Phone: 250.953.2033

Fax: 250.382.6539

Email: info@tourismvictoria.com

Web site: www.tourismvictoria.com

Flights from Vancouver to Victoria take about 25 minutes. The bus/ferry system is far more enjoyable, if not speedy. Shuttle buses transfer passengers from their hotels to the central depot and a larger bus, which takes about an hour to reach Tsawwassen where it embarks the ferry. The ninety-minute scenic crossing of Georgia Straight will take you past the Gulf Islands and may provide glimpses of eagles or a whale or two. When you arrive at Swartz Bay on Vancouver Island, you re-board your bus for the thirty-minute drive to the downtown Victoria depot.

BC Ferries: 1.888.223.3779

Pacific Coach Lines: 604.662.8074

Tickets can be purchased at the Vancouver Tourist Information Centre at 200 Burrard Street in Vancouver.

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian