On Iron Rails: Glimpses of Post Taliban Afghanistan

Review of The Bookseller of Kabul by Asne Seierstad

* * *

Introductory note, the reviewer's reminiscence of Afghanistan

During my travels through Afghanistan in 1968, buses were the main link between cities, since the country had no railway system. One such bus trip produced a persistent image that has flashed into recollection continually over the years. As an Afghan man climbed aboard the bus, a desperate woman, on her knees and sobbing beneath her burka, clutched at his clothes with both hands, imploring him not to leave. He turned, put his foot against her head, growled a single syllable, and shoved her backwards, leaving her slumped in a heap on the ground, like a sobbing bundle of laundry. The memory of that cruelty, that woman's anguish endures; the scene has been often recalled, stimulated by the various news reports coming out of the country over the years--the Soviet invasion, the civil war, the regime of the Taliban fundamentalists, the world wide outrage when the Taliban dynamited the 2000 year old Buddha images in Bamiyan, and the post 9/11 bombing of the country. The bus incident was again evoked while reading The Bookseller of Kabul, Asne Seierstad's fictionalized account of her extended stay with an Afghan family during the spring following the Taliban's defeat. Her novel reveals that although there is still no rail system in the country, Afghan society rides on the iron tracks of entrenched traditions, especially regarding the treatment of women.

* * *

Asne Seierstad, a Norwegian journalist, spent six weeks with the commandos of the Northern Alliance covering the offensive against the Taliban. After the fall of the Taliban, she visited a Kabul bookshop and became intrigued with the owner. Sultan Khan, as the author calls the title character, is described as "a living piece of Afghan cultural history: a history book on two feet." She saw the bookseller as an anomaly in a country with a literacy rate of less than twenty five per cent, and she was captivated by the stories of his tribulations during three different regimes.

After a dinner with his family, the author told Sultan that she would like to write about him and his family, and he graciously invited her for an extended stay at their apartment. It is surprising that there was room for the author during her sojourn in the spring of 2002. Over a dozen members of his extended family lived in Mikrorayon, in a Russian built five storey apartment complex. They had a four room flat, only three of which were lived in since the fourth was used solely as the family storage closet for clothes, books and other personal effects. Still, she was a welcomed guest and treated kindly; the family members were open with her and she soon became privy to their feelings.

The apartment building had been caught in the crossfire during the battle of the warlords during the civil war and had remained in a state of wreckage; over the years, it had been "pillaged and burned," the walls were pockmarked with bullet holes, and there were "gaping wounds where rockets once exploded." There had been no reliable running water in the complex for over 10 years; the first floors may have water for a few hours a day, but the pressure was too weak to reach the higher floors. Power might be available for about four hours every other day and oil lamps and wood stoves were the norm.

Rugs covered the stone floors and mats were used for sleeping at night and for sitting during the day. Meals were eaten on the floor and placed on a waxed cloth around which the family sat cross-legged. Holes in the windows were plugged with towels; the kitchen contained a gas stove and a hot plate. The bathroom, in a cubicle in the kitchen, was a hole in the floor with a tap nearby.

Afghanistan's per capita income at the time was US $280 and Seierstad emphasizes that the Khans were not a typical family; "They had enough money and never went hungry." She notes that a normal family would be large, illiterate, and involved in a daily battle to survive.

Seierstad found Sultan to be urbane, passionate, and magnanimous. Although readers will admire his defiance and liberal outlook, they will probably also find a lot to dislike about him. We soon learn that this authoritarian patriarch of the family, who often talked of the emancipation of women and the modernization of Afghanistan, has a cultural predisposition that is set on iron rails.

As the first male born into a large and poor family, Sultan was educated. His schooling was financed with the money received for the marriage of his older sister. As a child he helped support his family by firing bricks before and after school. Soon he started lying about how much he made and began buying books. He opened his first bookstore in Kabul during the 1970s and endured the persecutions of the Russians, the Mujahedeen, and the Taliban.

The invasion by the Soviet Union in 1979, led to the arrest, torture, and execution of tens of thousands of political opponents. Any publications deemed to further Mujahedeen ideology was banned and an attempt was made to suppress Islam. Sultan continued selling his books regardless of their contents and was soon incarcerated as a political prisoner for doing so. During his year in jail, he bribed guards to smuggle in books; he read extensively of his country's history and dedicated himself to promoting knowledge of Afghanistan's culture and history. After a second period in prison, this time for five years, he married Sharifa and they raised a family of four children.

When the Soviets withdrew in 1989 after a war that saw the death of an estimated 1.5 million Afghans, the regime in Kabul was still supported by the Soviets, and during the five year civil war between the Soviet regime and the Mujahedeen, Sultan fled to Pakistan with his family. On his return, he found that his store had been pillaged as was the public library in Kabul. Always the businessman, he was able to purchase rare books that had been stolen from the library.

Following the civil war, the Taliban established strict fundamentalist law and order. Sultan, "a moderate Muslim" who prayed once a day, had nothing but contempt for the illiterate Taliban. We are told at this transition point between regimes, "The war was over. A new war would start-a war that would trample all joy underfoot." A battle against Afghan art and culture was waged; one of their first targets was what was left of the Kabul museum. Murals, sculptures of Buddha, kings and princes were destroyed --"It took them half a day to annihilate a thousand years of history." In a scene reminiscent of Fahrenheit 451, the author describes the "religious police" armed with Kalashnikovs burning all books with images of living things. "These men considered anyone who loved pictures or books, sculpture or music, dance, film, or free thought enemies of society." After selling books deemed illegal and being warned several times, Sultan was arrested yet again. Defiantly, he raged at the officials of "The Department for the Promotion of Virtue and Extermination of Sin," "You can burn my books, you can embitter my life, you can even kill me, but you cannot wipe out Afghanistan's history."

An incident involving a carpenter who stole postcards from Sultan's store illustrates another facet of the title character. Jalaluddin, a carpenter who supports not only a family of seven children and a pregnant wife, but also an extended family consisting of his sister's five children, her unemployed husband as well as the carpenter's father, mother and grandmother. Two of Jalaluddin's children have polio and two other children have severe eczema. All are constantly hungry. Although we are told that Sultan returns every evening "with wads of money from his shops" and although he has packages containing thousands and thousands of additional postcards in storage, he is enraged at the carpenter's larceny and becomes obsessed with exacting justice, accusing the carpenter of attempting, as he says, to "usurp my life's work." During the days of the Taliban, the carpenter's hand would have been cut off. Now he faces three years in prison, which would leave his family destitute.

Desperate and remorseful, the carpenter prostrates himself before Sultan, kissing his feet and pleading for forgiveness; members of the carpenter's distressed family visit daily, tearfully begging for mercy, but Sultan is unaffected and pitiless. Even though according to law he could have withdrawn the complaint, he is relentless in his insistence that the man be imprisoned.

In spite of the title, this novel is not solely Sultan's story; Seierstad provides insights into the lives of many members of the family with whom she lives. Although her focus is on the women and how they are oppressed, we also get brief glimpses of two of Sultan's sons.

Aimal, Sultan's 12 year old son, is a victim of his father's ambition. He works for 12 hours a day, 7 days a week at one of his father's shops located in the dingy lobby of a Kabul hotel, and sells products like candy bars, soft drinks, jarred olives, and chewing gum--all well beyond their sell before dates, all smuggled in from Pakistan, and all sold at inflated prices. Called "the dreary room" by the reluctant young proprietor, the small dark shop is seldom frequented by customers. Denied the opportunity to go to school because of Sultan's inability to trust anyone other than family in his stores, Aimal lives a tedious and colourless life; we are told that "His heart bleeds and his stomach churns every time he opens the door." Sickly and cheerless, he is referred to as "the pale boy" by others in the hotel; he longs to run on soccer fields with school friends, but is condemned to be a child without a childhood while Sultan defers his son's education until what he calls "the foundation of our empire" has been built.

Sultan's eldest son, Mansur, is 17 and works in another of his father's shops. We learn of his disgust when a friend tells him of how he seduces beggar girls and war widows whose desperation for food or money is so great they will do anything. His friend's abhorrent behaviour serves to underscore the treatment of women in Afghanistan.

Mansur is sickened to hear his friend bragging about his exploits-"I take off the veil, the dress, the sandals, trousers. Having got there, it is too late for regret. It would be useless to scream because if anyone came to the rescue, the fault would lie with her, no matter what. The scandal would ruin her for life. It's easy with the widows. But if they are young girls, virgins, I do it between their legs." On one occasion, Mansur is in his friend's shop just after he is finished with a 12 year old girl in the back room and flees in revulsion when he is offered his turn. Sickened by the incident for days, he feels he has sinned for not stopping the shopkeeper.

To purge his sins and gain forgiveness, he makes a pilgrimage to the tomb of Ali, the much revered cousin of Mohammad, at Mazar-i-Sharif, a pilgrimage that had been banned while the Taliban was in power. He leaves the site with a feeling of being cleansed and with a renewed piety and determination to be devout. A week later, however, we learn that he "gave up the piety just a quickly as he had started. The pilgrimage was nothing more than an outing."

Although Mansur does reveal a compassionate side by his disgust at his friend's exploitation of the desperate, and although he urges his father to drop the charges against the carpenter, his verbal abuse of his mother prevents too much sympathy for this product of a centuries old mind set. At one point he yells at his mother to "keep your trap shut-go back to Pakistan." On another occasion when she asks him to remove his shoes, he tells her to go to hell.

Readers outraged at the behavior of Mansur's friend will undoubtedly have their anger escalate as they witness the subjugation of the women in Sultan's family. In her forward, Seierstad discloses that a continuing source of resentment during her stay with the family was the treatment of women by men; she became aware that in Afghan culture, "The belief in male superiority was so ingrained that it was seldom questioned."

Old customs die hard, Seierstad observes, "Throughout the centuries Afghan women have had to put up with injustices committed in their name." It is soon apparent that the engine of modernization anticipated by the bookseller will be slowed by the heavy box cars of long established beliefs.

The author chose to wear the burka not only for the anonymity it provided on Kabul's streets, but also to experience "what it is like to be an Afghan woman; what it feels like to squash into the chockablock back rows reserved for women when the rest of the bus is half empty, what it feels like to squeeze into the trunk of a taxi because a man is occupying the backseat...." She soon learned how imprisoning the garment was, how hot, how heavy on the head, and how difficult it was to see through; "Burka women are like horses with blinkers: they can look only in one direction. Where the eye narrows, the grille stops and thick material takes its place; impossible to glance sideways. The whole head must turn; another trick by the burka inventor: a man must know what his wife is looking at." Seierstad expresses how much of a relief, how liberating it was, to remove the imprisoning burka when she returned to the apartment.

Although burkas were banned for use by public servants in 1961, they were reintroduced and made mandatory by the Taliban in 1996. Still, in the first post-Taliban spring, few women abandoned the burka. Even though Kabul has almost daily sunshine, many women suffer from vitamin D deficiency, blocked as they are from the curative sunshine.

During the days of the Taliban, it was decreed "Women must not make it possible to attract the attention of evil people who look lustfully upon them. A woman's responsibility is to bring up and gather her family together and attend to food and clothes." The Taliban had forbidden women from wearing shoes with solid heels since it was believed that the sound of women walking might distract men. Women were also forbidden to use nail polish and those who disobeyed had the tip of a finger or toe cut off.

So entrenched was the tradition of female inferiority, the author notes, "The liberation of women during the first spring following the fall of the Taliban has on the whole restricted itself to the shoe and nail-polish level, and has not yet reached further than the muddy edge of women's burkas." After a visit to a hammam, the women are described as putting on the same clothes that they wore before their bath; Seierstad departs from the objectivity that characterizes her novel with the words, "The women's own smells are soon restored. The smell of old slave, young slave."

Through the character Sharifa, Sultan's first wife, the situation faced by Afghan women is clearly personified. A qualified Persian language teacher in her early fifties, she is distraught at the news that Sultan is taking the illiterate 16 year old Sonya as his second wife. So intense was the disgrace and sense of inadequacy she felt, she fabricated the excuse that a polyp had developed in her womb and explained she had been advised by her doctor that intercourse would kill her; she said it was at her urging that Sultan found a second wife. Her imaginary ailment served to mitigate the embarrassment and humiliation she experienced.

Sharifa obeyed Sultan not only when he demanded that she attend the engagement celebration, but also when he insisted that she put the rings on both his and Sonya's fingers. After bearing him three sons and a daughter, she was suddenly a "superannuated wife," but Sultan was still her master.

During the first year of Sultan's new marriage, Sharifa lived with them and was essentially a housekeeper, cooking, serving, and cleaning. Especially painful was enduring the sounds that came from the bedroom, "sounds that cut her to the heart." While it is not abnormal for a man to take a second wife, other husbands, unlike Sultan, struck a balance in their relationships with their wives and showed no favouritism.

Although Sultan had returned to Kabul from Peshawar soon after the fall of the Taliban, and gradually brought his family back to join him; Sharifa and her daughter were left behind to look after the house where his most precious books are kept. In a moment of introspection, Sharifa reveals that "Sometime she hates him for having ruined her life, taken away her children, shamed her in the eyes of the world."

While Sharifa was in Peshawar, watching over Sultan's stash of books and awaiting her master to reunite her and her daughter with the rest of the family in Kabul, the community of Afghan refugees was buzzing with gossip regarding a 16 year old girl who had exchanged love letters with and fallen in love with a boy not chosen by her family. The young girl had dared to meet with him in a public park for a few stolen moments, and had been seen getting into a taxi with the boy. When she returned home, she was beaten and locked in a room and later whipped with a wire while being held by aunts, her punishment for bringing such disgrace and stained honour to the family.

The incident reminded Sharifa of her neighbour in Kabul who was married at 18 to an Afghan from overseas whom she had never met and was over 40 years her senior. When the husband returned overseas to make visa arrangements for his new bride, she had an affair. When it was discovered, the groom's family had the marriage dissolved and the girl was locked in a room until a punishment could be determined. Her mother sent her brothers to the room with instructions to suffocate her with a pillow. At her funeral, it was explained that the girl had been killed accidentally when a fan had short circuited. The "accident" served to rescue the family's stained reputation. During Taliban rule, adultery was punishable by death through stoning.

Sharifa is left with no idea when Sultan will come to Peshawar to get her; daily, she prepares meals for him on the chance that he will arrive. She lives like a divorced woman, but "Divorce is not an alternative. If a woman demands divorce, she loses virtually all her rights and privileges. The husband is awarded the children and can even refuse the wife access to them. She is a disgrace to her family, often ostracized, and all property falls to the husband." On the day that Sultan finally arrives, she lays out the meal; he complains about the quality of the plates and insists that she change them.

Bibi Gul, Sultan's mother, the Rubenesque matriarch of the household and "the second in command," seems to spend her days drinking tea, brooding, and furtively eating the almonds and sweets she has secreted throughout the house. Her predominant function is as the guardian of "the family's morals-in practice, the morals of the daughters." Married at the age of 11 to a man 20 years her senior, Bibi Gul had 13 children, two of whom died in infancy, a not uncommon occurrence in a country with the world's highest infant mortality rate; one quarter of Afghani children die before the age of five. Her last born son was given away to a childless relative 20 days after his birth, since in this culture, "A woman gains stature by being a mother, especially of sons. A sterile woman is not valued."

We learn that her first few years as a child bride were spent crying and that her life only gained meaning when she was 14 and her first child, her daughter Feroza, was born. The 20,000 afghanis received when the 15 year old Feroza was married to a 40 year old, had been used for Sultan's education.

It is the custom for one of the women in an Afghan family to make the marriage proposal and marriage is mainly within the tribal clan, often between relatives, predominantly cousins. Love is rarely a marriage consideration; we are told "Young women are above all objects to be bartered or sold." In the case of Sultan's sister, Shakila, Bibi Gul looked beyond the dowry and insisted from those making marriage proposals that her daughter be allowed to continue her schooling, and then as time passed, to continue with her teaching profession. As a result, Shakila remained a spinster into her thirties.

When her daughter was finally married, to a recent widower with ten children, one of the novel's few references to happiness occurs, not through the elation of marriage on the part of either the bride or the mother, but rather Bibi Gul's tears of joy elicited when a bloody cloth was displayed reverently after the wedding night. One wonders if the happiness was from relief that the bride would not be returned in shame and humiliation.

Couples do fall in love, of course, but such relationships are frequently doomed. Before her marriage to the widower with the ten children, Shakila did fall in love with a fellow teacher, Mahmoud, who was already a part of "an arranged and loveless marriage." The two secret lovers hoped that Shakila could become Mahmoud's second wife, and for a time there was hope in both their lives. Mahmoud was unable to convince a female in his family to arrange a marriage to someone outside the clan and when Shakila attempted to broach the subject with Bibi Gul, the conversations were always dismissed. The clandestine lovers infrequently saw each other and always in relationship to work; while phone lines were operating, they would communicate privately. When the civil war broke out, Shakila fled with her family to Pakistan and when she returned to Kabul, women were prohibited from teaching. Eventually Mahmoud was transferred and for Shakila "life lost all colour." It is difficult to be optimistic that her marriage to a husband with 10 children will brighten her life; nevertheless, she will be permitted to continue teaching and perhaps find happiness in her profession.

Shakila's disappointment in love is the norm:

In Afghanistan a woman's longing for love is taboo. It is forbidden

by the tribes' notion of honour and by the mullahs. Young people

have no right to meet, to love, or to choose. Love has little to do

with romance; on the contrary, love can be interpreted as committing

a serious crime, punishable by death. The undisciplined are cruelly

killed. Should only one guilty party be executed, it is invariably the woman.

Even though Sonya, Sultan's second wife, was a reluctant bride, "A young girl has no right to have an opinion about a suitor." Until their marriage, the 16 year old always referred to her husband as "Uncle Sultan." We learn that at the prospect of marrying Sultan, "She was petrified, paralyzed by fear. She did not want the man but she knew she had to obey her parents. As Sultan's wife, her standing in Afghan society would go up considerably. The bride money would solve many of her family's problems. The money would help her parents buy good wives for their sons." As was the custom, a payment for Sonya was negotiated; Sonya's price was "a ring, a necklace, earrings, and bracelet, all in red gold; as many clothes as she wanted; 600 pounds of rice, 300 pounds of cooking oil, a cow, a few sheep, and 15 million afghani, approximately $500." Sonya has given birth to a daughter and is again pregnant; at the end of the book she reveals her fear that if the second baby is also a girl, Sultan will find a new wife.

It is clear that the novel is really the story of Leila, Sultan's unmarried 19 year old sister and Bibi Gul's last born daughter. It is through Leila's character that the plight of women in Afghanistan is epitomized and it is the predicament of Leila that most affected the author. She is described as being at "a standstill in the mud of society and the dust of tradition."

Leila learned English while she was a refugee in Pakistan where she went to school, and this language link probably accounts for the insights Seierstad is able to gain regarding Leila's feelings. Leila feels like an outsider in Sultan's house and is treated that way by Sultan's sons. Because she is the youngest and unmarried, she is a servant; "She has been brought up to serve, and she has become a servant, ordered around by everyone."

Leila appears to accept her lot passively, yet she reveals her true feeling to the author; "I'm going mad. I cannot stand it any longer. I don't belong here." It is her dream to follow the path of her sister, Shakila, and become a teacher; her attempts to find a teaching job, however, are constantly blocked by bureaucracy. Seierstad is direct in describing Leila's situation; "Leila is a true child of the civil war, the mullah reign, and the Taliban. A child of fear. She cries inside. The attempt to break away, to do something independent, to learn something, has failed."

Leila is portrayed as being like Cinderella; for a time, though, there is a prince in Leila's world and Leila has the misfortune of falling in love. She shares clandestine letters with Karim, a man outside the family clan and a friend of her brother. Colour enters into Leila's world; "The letters cause her to dream. About another life. ...Suddenly there is a world inside her head she never knew existed."

The feelings she has for Karim and the promise they bring for a new life create inner conflict for Leila since she has been raised as a prisoner of tradition, traveling on the iron tracks of custom. She attempts to deny her emotions; "Feelings are a disgrace, Leila has been taught." Even though she considers Karim to be her saviour, she is still a victim of convention, and tells him, "My family will decide whether I like you or not."

Leila's hope for a new life is soon shattered when it is learned that Wakil, the widower with ten children that became the arranged husband of Shakila, has already chosen Leila as a wife for one of his sons. Wakil convinces Mansur to plant suspicion in Karim; Mansur insinuates to Karim that he knows there is something about Leila that would change his mind about marrying her. Mansur justifies his duplicity by saying, "Wakil was family, Karim was not"

The deception works and Karim is scared off; Bibi Gul agrees to the proposed marriage with Wakil's son. Leila's brief flame of hope is extinguished and she realizes that her life will be exactly the same as it was--a drab existence of servitude. The novel closes with a poignant description of Leila's future:

She feels her heart, heavy and lonely like a stone, condemned to be crushed forever....

Her crushed heart she leaves behind. Soon it blends with the dust,

which blows in through the window, the dust that lives in the carpets.

That evening she will sweep it up and throw it out into the backyard.

In her forward, the author states that the book gives her impression of the first Kabul spring after the defeat of the Taliban and "those who tried to throw winter off, grow and blossom." For Leila, however, the chance to flower is blighted by the frost of social mores. She will live a life of suppressed hopes. She will sweep away the shards of half formed dreams and join the rest of the joyless Afghan women who ride their wintry lives on the rails of tradition.

* * *

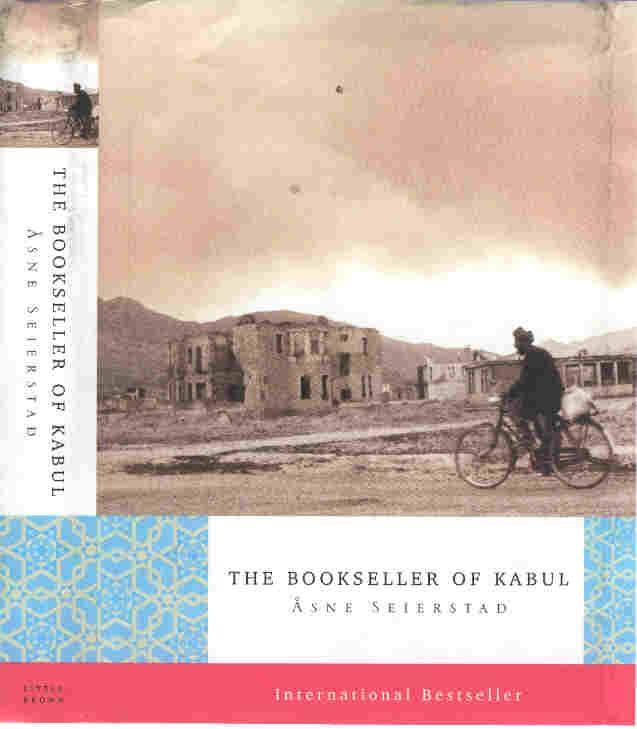

Review of The Bookseller of Kabul by Asne Seierstad

(Little, Brown and Company: 2002)

Translated by Ingrid Christophersen

Jacket photograph © Thomas Dworzak / Magnum

* * * * *

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian