Bright Lights, Big Congee

"What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter." -- Henri Matisse

That a book is an international bestseller is sadly no guarantee of its quality. But a book that has been banned and publicly burned in China at least has the merit of having irritated the fickle and prudish Chinese Communist Party, which may now regret that it also banned the works of China's only Nobel Laureate in Literature, Gao Xingjian. But Shanghai Baby by Chinese writer Wei Hui has been added to the Party's own Index Librorum Prohibitorum not for its politics, as was the case with Mr. Gao, but for its morals, or lack thereof.

Its narrator and protagonist Nikki engages in (and thoroughly enjoys) illicit sex, and even fantasizes about being raped by tigers. She smokes. Her boyfriend is an impotent morphine addict and both of them are addicted to nightly sleeping pills. And what is infinitely more treasonous, she is a writer of bourgeois novels, and her heroes include libidinous Henry Miller and Marguerite Duras. Indeed, there is almost nothing recognizably Chinese about Nikki, and apparently some critics have dubbed her creator "a slave of foreign culture" -- proof that China's perestroika was not accompanied by a glasnost. Even Nikki uses the notorious phrase "foreign devils" to refer to non-Chinese, albeit somewhat tongue-in-cheek. And the one American in the book receives a deranged scolding from a Serb as the bombs rain down on Belgrade during the NATO campaign. At least one of those bombs, you may remember, fell on the Chinese embassy, which is perhaps why Wei Hui seems to approve of the Serb's tiresome fit. Much thanks, she seems to say, for the American culture upon which I am feebly dependent, but America itself disgusts me. The double standard is pedestrian.

The plot of Shanghai Baby is negligible. Nikki cheats on her boyfriend Tian Tian by having wild and emotionally vacuous sex with a piece of German beefcake named Mark (I almost wrote Marx.) Unfortunately, or fortunately, Mark is married. Tian Tian suspects that something is up so he goes on a trip to the south, where he starts on the dope. Nikki goes to see him and convinces him to enter a forbidding detox center. She then returns to Shanghai alone and continues sleeping with Mark. But then he needs to return to Germany. Tian Tian comes back, learns definitively of Nikki's infidelity, and resumes shooting up until he dies. As all of the main characters in the novel are wealthy, one is put in mind of Bret Easton Ellis' Less Than Zero, a thoroughly depressing novel about rich, self-absorbed kids destroying themselves in a way that is "utterly sexy" -- to borrow Nikki's phrase for herself and her kind. Both novels are part novels, part ads for Calvin Klein.

Like Ellis, Wei Hui cannot resist including in her novel certain labels of popular culture, whether it is Vidal Sassoon or the film Titanic, or, you know, "Andy Lau's line in that Ericsson ad." Such things are perhaps to be expected in a bestseller, but they automatically date it. In five or ten or twenty years no one will know what Wei Hui is talking about when she says that she felt "sad and utterly hopeless, like the terrifying sounds out of Boogie Nights." (Having never seen the film myself, I don't even know what Wei Hui is talking about now.) For those few of us whose main source of entertainment continues to be the lowly book, one almost expects Shanghai Baby to come with a CD and some videos, to make meaningful its manifold references to songs and films. Each of the novel's thirty-two chapters is introduced by one or more epigraphs, all of which seem to be straining to convey some deep idea without quite making it. They range from "Love will tear us apart" by the suicidal singer Ian Curtis to Descartes' "I think, therefore I am." Nikki lavishes praise on herself for her "metaphysical" thoughts, but I see very little metaphysical (and nothing at all original) in the novel's closing line: "Who am I, indeed? Who am I?" One is tempted to reply, "You are Nikki and this is a book and that is an elementary introduction to Wittgenstein," who once wrote: "Philosophy is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language."

Like Nikki's hero Henry Miller, Wei Hui writes graphically (and for the most part convincingly) about sex and the various fluids and explosions entailed by it, including Nikki's onanism and a very Milleresque bout in a toilet stall. Both authors had their books banned in their homelands for similar reasons (Miller's were illegal in America as late as the 1960s.) And if the translation is to be believed, Wei Hui's writing style resembles Miller's, an ecstatic I-am-on-fire fluency that is usually a great joy to read and probably even more fun to write. Nikki anyway seems to share Miller's lust for life, and his lust, and many of the problems caused by lust, including a willful and contemptible ignorance of how lust can make your life into a confused mess. I worry for China's young. I hope that they do not repeat the stupidity and spoliation of the Sexual Revolution. I hope at any rate that Mark was wearing a condom when he, strictly speaking, rapes Nikki (how else is one to interpret her initial cries of "No" and "No way"?) I have read that an alarming proportion of Germans abroad do not wear condoms, and this piece of wisdom from Nikki only adds to my concern: "Many gay or bisexual men have a special fuzzy, sort of tenderness that one finds in small animals, but I'm always aware of the Aids risk." Is she aware of the Aids risk from her junkie boyfriend or her impulsive, promiscuous German? Well, maybe this is the author's point, a way of demonstrating the recklessness of her generation ("those of us born in the 1970s"), without necessarily approving of it. But she does approve of it. Indeed she flaunts it in the face of the sexless and lifeless creatures created by Mao, who died in 1976. But it's a pity that Nikki is so unhappy being rich and free. Maybe she can learn something from the Americans about that.

It is telling that virtually the only politics in the novel are those already mentioned: China's anger at America for those nasty little bombs. The Clinton-Lewinsky scandal gets a brief mention. Only a statue of Chairman Mao appears, and Wei Hui makes a delicate reference to a "displaced" intellectual (read: "banished"). Nikki and her friends are not interested in politics, as their Cultural Revolutionary parents were. Rather they are interested in staying or becoming rich, having fun, and getting laid. Oh, and art -- or Art. Tian Tian is a painter, as is a man with the curious name of Ah Dick, who dallies with a woman named Madonna. The names of Matisse and Dali and others get dropped quite frequently.

Needless to say, rich folk sitting around gabbing about dead and largely forgotten visual artists from Europe is pretty well-trodden ground, thanks to the Europeans, and while there may be something subversive about Wei Hui's being "a slave to foreign culture", I don't see anything very interesting about it. Why the fuss about this copycat book? Does it lend any credit to contemporary Chinese literature that it can update Tropic of Cancer sans prostitutes seventy years after Miller published it? Shanghai Baby is set in Shanghai, true, but it could almost be set anywhere, as cities all over the world grow increasingly alike, and as Nikki cruises around in a VW and decides that House and Hip Hop music are "totally cool". If you need any evidence that the East-West dichotomy is outdated, this novel may be it.

Maybe I exaggerate. There are some remnants of Chinese culture here. Or pseudo-Chinese culture. It is interesting, for example, that Nikki, a materialist, complains about "this fucking material age". She is in the position of the Nike-wearing anarchists in Seattle who went about destroying Nike outlets. But I have a sneaking feeling that by materialism she actually means capitalism. Mao, after all, was nothing if he was not a materialist. And the Chinese have traditionally eschewed the otherworldly, thanks to Confucius. Indeed, what was China at the height of its imperial glory but a sprawling testament to material things?

As for real China, Shanghai Baby is peppered with Chinese words, like laowai, which apparently means foreigner, and guroupi, which apparently means groupie. Like Mao, Wei Hui uses the word "dog-fart" as an insult ("dog-fart lifestyle"). Nikki enjoys hand-pulled noodles and congee, a rice broth or porridge. She dances half-naked while gazing at Asia's tallest building, the Oriental Pearl TV Tower. Her parents are characteristically overprotective. Her lover Mark confuses the Chinese words for "wallet" and "foreskin" -- presumably a tone error. And she makes all kinds of generalizations about both Asians and Caucasians, some less wrong-headed than others. (She says that cleft chins are "characteristic of Westerners".)

Literary critic James Wood has made a name for himself by blasting what he calls novels of information, and he has coined the genre "hysterical realism" to encompass them. He would not like Shanghai Baby. While Wei Hui's language and subject matter are sometimes thrilling, and the novel as a whole is enjoyable to read, her emphasis seems to be on conveying a way of life rather than making us care about it. Only Nikki has depth as a character, but she herself is so shallow that she is no more captivating than a jumble of billboards seen from a passing car on a freeway. Of course there are countless Nikkis in the world -- neurotic young women who love themselves so much that their only lovers are artistic drug addicts that have been abandoned by their mothers, or strapping athletes who want nothing else but sex. But that Nikki may be an archetype does not make her any more agreeable. Wei Hui may be a fresh new voice in China, but to an American accustomed to women as liberated and aggressive as they are insecure and alone, her voice is staler than the air in Shanghai.

* * * * *

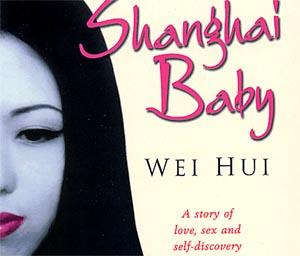

Review of Wei Hui's Shanghai Baby, Robinson, 2002.

* * * * *

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian