Colonel Cassandra

The most enjoyable phrase in the English language is, as we all know, "I told you so." For decades, the American soldier Edward Lansdale banged on about why America was losing the Vietnam War and how it could win. His reward? Ostracism and deaf ears, so that in later life he could justifiably say that the U.S. Army had "lost touch with reality."

Lansdale is no obscure or forgotten figure. He is the model of Hillandale, the harmonica-playing spook of The Ugly American. And practically everyone except Graham Greene and Lansdale himself believes that he was the model for Greene's Quiet American Pyle. A major general by the time of his death, Lansdale was consulted (though not always liked) by those most responsible for the conflict in Vietnam. JFK wanted to make him an ambassador, while neither Defense Secretary McNamara nor the run of bomb-happy generals liked either his ideas or his attitude. But history has been kinder to the "Ugly American", as his fundamental idea, that Vietnam was foremost a political and not a military conflict, has been elevated from the ravings of a Cassandra to a more or less indisputable fact.

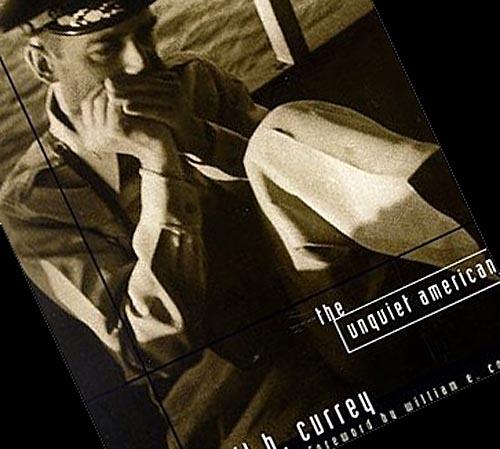

Not that Lansdale was a martyr, or some Gandhi figure come to insert flowers into the barrels of AK-47s. Sometimes employed by the CIA, Lansdale like all spies was a consummate liar and trickster, and would prevaricate about his past doings until his death in 1987. Using so-called psychological warfare, he manipulated the elections in the Philippines to favor the pro-US President Magsaysay and to alienate the Communist Huk rebels, a feat that would earn him the title "Colonel Landslide." The intention all along was to assure, as Currey writes, "that the new nation would remain an economic colony of the United States." Lansdale wrote some of Magsaysay's speeches; on one occasion, he even punched the Filipino leader to prevent him from reading an alternative speech. A king-maker and nation-builder, Lansdale fully swallowed the myth that the Communist bloc and the "free world" were engaged in a death struggle; and that the free world, as represented by documents like the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, clearly represented the better option. And he was hardly shy about saying so. Thus does Cecil B. Currey, a veteran and military historian, title his biography of Lansdale The Unquiet American.

The variation on Greene's phrase is, I think, just, although I can't help but mention that Currey lifts from Greene the phrase "impregnably armored" ("by his good intentions and his ignorance" - Greene; "by his ignorance and his political prejudices" - Currey.) Lansdale is more Hillandale than Pyle, for Pyle is many things that Lansdale was not: diffident; unmarried; Ivy League-educated; ignorant of Vietnam. Greene apparently disliked Lansdale: Currey relates a scene in which Greene provokes some French soldiers into booing him. But the British journalist Fowler likes Pyle as a person even though he detests his machinations. As Greene rightly protested, Lansdale would have been a poor choice to "represent the danger of innocence": former CIA director William Colby deemed Lansdale to be among the top ten spies /of all time/. Pyle, in contrast, strikes one as an amateur, especially given that his enemies assassinate him. On the other hand, Lansdale does commit the very Pyle-like mistake of assuming that the Filipinos "share the same ethics we do...ideals, including democracy." Everybody is an American. Really.

Currey's history has been written under the aegis of something called The Association of the United States Army, one of whose stated goals is "the promotion of proper recognition and appreciation of the profession of arms," as if FOX News and Band of Brothers were not enough. One would therefore expect the book to be oozing with pro-military or pro-American bias. Surprisingly, it is not. Soldiers have been some of the best and most objective writers: Gertrude Stein once praised the Romanesque prose of Ulysses S. Grant.

Only occasionally does Currey slip. When Lansdale meddles in the Philippine election, Currey puts "meddling" in quotes to suggest that it was not meddling. In fact, Lansdale had printed a number of leaflets urging the Huk rebels to boycott the election. The Huks went along, and thus lost any hope of gaining legitimate political power. This is meddling. So is manipulating the appearance of ballots to favor one candidate. So is funding the publication of pro-US and anti-USSR articles in Filipino newspapers. So is the mysterious appearance of US warships in Manila Bay a few days before the election. So is funneling US money to the Magsaysay campaign. (Lansdale denied doing so; Currey demurs.) Lansdale was in the Philippines precisely to meddle. Hence "Colonel Landslide" and top-ten spy.

Currey does not, however, put the word "menace" in quotes when he writes of the "Communist menace", even though Lansdale's meddling was a menace in its own right. Currey also refers occasionally to "this nation", as in: "Many men have worked for the intelligence services of this nation and remained unsung." For the 95% of the world's population that is not American, it should be said that by "this nation" Currey means the United States. The slip is a subtle one, but it speaks volumes. So does the name of the propaganda arm of the OSS (the precursor to the CIA): "Moral Operations". So does Currey's reference to "a time when the US actually interfered in the political process of a foreign country." There was never not such a time. Every country interferes with the political processes of foreign countries.

Lansdale's contribution to military thinking is arguably not novel. "Know thine enemy" is as old as history, which makes it all the more astounding that the American leadership tended to favor Curtis LeMay's "Bomb thine enemy." Lansdale liked Asians. Ultimately he would make one, a Filipina, his wife. He studied the writings of Mao and the Viet Minh's General Giap. Though he would always have trouble learning languages, he collected Vietnamese folk songs; ate Filipino food; wined and dined and - most importantly -- listened to his Asian allies while most Americans treated them with condescension. Early on, he learned why the Communist insurgencies were so successful despite their excesses. Filipino villagers that had witnessed Communist atrocities tended to recall not the atrocities but how "polite and thoughtful" the guerillas were, whereas the equally brutal government troops tended to be pushy and arrogant. (There was a corresponding disparity between the behavior of the Viet Cong and the South Vietnamese army.)

Lansdale believed that to win hearts and minds it was insufficient, even counterproductive, to kill Communists or belittle Communism; instead one had to offer a better alternative (Lansdale formerly worked in advertising.) He would repeatedly say that the Vietnamese were "real live human beings" and not statistics, gooks, or insects. Then again, Lansdale himself made the chillingly Kurtz-like assertion that if the "only alternative" is genocide ("to kill every last person in the enemy ranks"), he was not "morally opposed" to it; nevertheless he thought it "humanly impossible." He believed that the indiscriminate American retaliation to the Tet Offensive signaled the end of the war. "They [now] hated all Americans," he complained.

The back cover of Currey's book carries a blurb from Neil Sheehan, author of the Vietnam War history A Bright Shining Lie. It says that South Vietnam "was the creation of Edward Lansdale." This is only slightly an exaggeration, and it belies the usual claim that South Vietnam was a well-established entity to be defended against Communist aggression. Instead, defense and state creation occurred simultaneously, the point being to counter the probability that the Communists (dominating the more populous North Vietnam) would win the countrywide elections stipulated by the Geneva accords. Yet again, the US subverted democracy in the name of democracy. When Diem was named premier by the foppish emperor Bao Dai in 1954, he had, according to Currey, "no political base at all." It fell to Lansdale to create one. But by the time he had, the American leadership was already through with Diem and would back his assassination in 1963. Lansdale lost not only a friend, but also a decade's progress. His career is a valuable lesson in how government agencies can work against each other with disastrous results.

It also offers lessons in the super-secrecy of what some writers have called the American "national security state", particularly that of the National Security Council, the CIA, and the "Office of Policy Coordination" (OPC) - all more or less unaccountable bodies created a few years after the end of World War II. Not until 1982 was the existence of the OPC (for which Lansdale worked) revealed; and to this day, the CIA evades the constitutional requirement that government agencies declare their budgets to Congress. Abuses of this power led to the formation of the Senate Church Committee, to which Lansdale probably lied about his knowledge of plans to assassinate Fidel Castro. As a historian, Currey complains that some of Lansdale's reports from Southeast Asia are unavailable "presumably in the 'national interest'.... Such devotion to keeping the public ignorant is laudable indeed!" But the CIA itself, which is predicated on maintaining public ignorance, doesn't seem to bother him, even though it was behind much of the murderous shenanigans of that time, including the secret war in Laos.

Though Lansdale took full advantage of this apparatus of secrecy, he was candid when it came to the shortsightedness of American realpolitik in Asia. In reference to the American move to link Diem exclusively with his brother Nhu's Can Lao party, Lansdale remarked, "[W]e don't seem to have very long memories or enough feeling of responsibility for our acts.... I cannot truly sympathize with Americans who help to promote a fascistic state and then get angry when it doesn't act like a democracy." The words remain relevant. But it may be that Greene was right to fashion the Quiet American as just another holy oaf incanting platitudes about democracy while remaining wholly ignorant of the country where he operates. Lansdale died but the Pyle archetype endures. And so much the worse for those people believed to be waiting breathlessly for representative government, when all they want is, as Greene put it, "enough rice" - and fewer bullets.

- The End -

Review of Cecil B. Currey's Edward Lansdale: The Unquiet American, Brassey's, 1998.

* * * * *

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian