Freedom of Information Acts

If you have never lived in a totalitarian state, you can barely begin to appreciate the freedoms you take for granted. Consider Laos, where I presently write. Its totalitarianism is a fairly gentle one. But of its capital's few bookshops, one is a state-owned venture selling what appear to be only drab, revolutionary tracts and technical manuals, as well as framed portraits of representatives of the country's only legal political party, the LPRP. Or take Burma. Recently I accompanied an American friend to a newsstand in Bangkok where he purchased assorted Western news weeklies. He was intending to smuggle this contraband literature into Burma and give it to friends there. He succeeded, but not without a fright.

China's censorship may be no more strict than that of Laos or Burma, but its enforcement probably has been, especially during the Cultural Revolution when even family members were taunting each other as "enemies of the state". Such is the backdrop of Dai Sijie's delightful little novel Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress, in which the banned works of the French author are worth their weight in gold, and possessing them can bring torture or imprisonment.

Set in a re-education camp, the story revolves around two young men and best friends: the narrator and one Luo. Their hard lot includes working the seam of a menacing coal mine and hauling excrement around on their backs. Worse, they consider themselves to be part of the class of prisoners called "three-in-a-thousand", referring to the odds of their release. Their crime? Simply that their fathers were "intellectuals" -- one a doctor and the other a dentist. Such was the twisted logic of Mao's China, in which people became useless and powerless in proportion as they were useful and powerful.

The ignorance of the camp's residents is made plain from the beginning. Confronted with a violin, the camp headman "solemnly" decides that it must be some kind of toy. When the narrator protests that it is actually a musical instrument, he is asked to play something. He chooses Mozart. Unfortunately "music by Mozart or indeed any Western composer had been banned years ago." So Luo declares that the Mozart tune he will play is called Mozart is Thinking of Chairman Mao.

Meanwhile the only books available were "by Mao or his cronies, and purely scientific works." Even Chinese classics such as The Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Dream of the Red Chamber had been banned, and "the Western literature sections of the bookshops were devoted to the complete works of the Albanian Communist leader Enver Hoxha." Enver Hoxha. So when the two friends discover that a poet's son named Four-Eyes has a suitcase full of books, they are determined to get their hands on them. When the loss of his eyeglasses prevents Four-Eyes from doing his work, the two friends offer to do it in exchange for one book. Four-Eyes reluctantly agrees, and soon they have a copy of a Balzac novel translated into Chinese. And thus their obsession begins.

Enter the seamstress. Both men have the hots for her. She is already a free spirit ripe for a catalyst like French literature, and both men use it to try to win her over. Luo is more ardent and more successful, even though the seamstress confesses a partiality to the narrator's storytelling abilities. (The camp's headman had arranged for both men to travel to a nearby town in order to watch films there -- mostly North Korean and Chinese propaganda films -- and then return to reenact them.) Eventually Luo manages to make love to the seamstress -- while standing! While standing, grumbles the jealous narrator. But neither of the men realize that French literature has awakened the seamstress's sense of her worth, beauty and...liberty.

The novel is an indictment not only of Mao's China but also of the cruelty of the Chinese toward each other. Though a love story, Balzac is an exceedingly violent one, and a reader of it will begin to understand the viciousness of a Chinese mob. Even the narrator gives in to sadistic urges when he is charged with propelling the makeshift drill used by Luo, the dentist's son, to fix the camp headman's teeth. (Apparently the slower the drill's rotation, the more painful it is. So the narrator makes it rotate as slowly as possible, to make up for all the abuse he has received at the headman's hands.)

But like Gao Xingjian's Soul Mountain, the novel is also a celebration of the Chinese peasant's (so like the French peasant's) earthy humor and sexuality -- qualities that Communism tried but failed to suppress. The young men propose to collect the folk songs of the mountains, because their publication will earn Four-Eyes a ticket out of the camp. Four-Eyes expects songs that celebrate labor or something else pleasing to the Party. Instead he learns that the songs are mostly ditties alluding to illicit sex (between a "young nun" and an "old monk", for example.) Irritated, Four-Eyes revises the ditties so that they sing the virtues of the proletariat. This so enrages the narrator that he assaults Four-Eyes. But the books keep coming, and the narrator betrays a particular attachment to Romain Rolland's Jean-Christophe. To it he gives the highest praise a work of literature can garner: "once you read it, neither your own life nor the world you lived in would ever look the same."

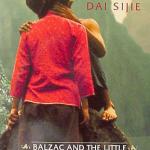

Given the author's adulation of French literature and the French worldview, it should be little surprise that like Mr. Gao he now resides in France, that country of exiles par excellence. And apparently it is the French who have helped turn the novel into a film directed by Dai Sijie himself, a filmmaker in addition to an author. The film joins a growing number centering around works of literature that virtually no one reads anymore (Herodotus's Histories in The English Patient, for example), as if only film can save literature from destruction. Ironically, the narrator is in some sense preserving film by means of literature when he reenacts his propaganda films.

It may be that only in nominally free countries is the written word so undervalued, whereas in other countries it remains a vital source of inspiration and subversion. If you have known only the desiccated writings of Karl Marx or Mao, even Balzac would be a bombshell -- to say nothing of Miller, Joyce, or Nabokov (all authors whose works have been banned even in America.) To read these authors would amount to poking a stick into "the all-seeing eye of the dictatorship of the proletariat", as Dai Sijie calls it. For despite its many virtues, the proletariat is usually more illiterate than not. And there are few things more frightening than a dictator that does not read.

* * *

Review of Dai Sijie's Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress, Vintage, 2003.

* * * * *

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian