White Horse Temple

Horse shoes are lucky charms in some countries. In Hanoi, a horse's hoof prints were once considered good luck and the city honors a white horse as its patron saint. A temple to this revered spirit, the White Horse or Bach Ma Temple (in Chinese, formerly used by the Vietnamese for literary or poetic purposes, bach means white and ma is horse), is located at 76 Hang Buom Street in the city's old quarter.

Many years ago, Hanoi was swampy and several small rivers ran through the area. The White Horse Temple originally lay on the bank of the To Lich River which is now filled in but used to flow into the Red River. The To Lich was once quite wide. At certain times of the year it flowed into the Red River and at other times it flowed away from the river to the west. As a result of the confluence of the two rivers, the currents became choppy and hazardous for ships. So a temple was built to the river god. There were several myths about the powerful spirits who exerted power here. One was the saint To Lich who is said to have been a virtuous and educated man. When he died, the river and the area near where he lived were called To Lich. He was worshipped as the earth god of the banks of the river. Whenever the land was disturbed by digging for new building, his permission was required and offerings were made to him. If the spirit was not pleased about the construction, the project would be doomed. In addition to To Lich, there was an earth god called Long Do or Dragon's Belly (long means dragon and do means navel).

From 866 to 875, when the area of Hanoi was part of the Chinese province of Giao Chi, a Chinese mandarin called Cao Bien was the governor. When Cao Bien began construction of his walled administrative quarters, he had heard local folk tales of an old man with a white beard who was the area's earth god. One day while inspecting his construction site, Cao Bien saw billows of clouds twinkling like stars in five colors. The earth became cold sending chills through Cao Bien. A bearded man on a golden dragon appeared among the clouds . He wore boots, a red hat and purple robes. Suddenly the air was filled with an intoxicating fragrance and heavenly music was heard. Cao Bien understood it was the powerful spirit who inhabited the earth and who required offerings and prayers if a project in his domain was to succeed. That night in a dream, the old man told Cao Bien, " I am Long Do, I saw that you were building a citadel so I came to see you."

Instead of submitting to the power of the indigenous spirit, Cao Bien tried to exert a superior magic. In an attempt to exorcise the spirit and take control, he buried bronze and iron charms under the temple. These talismen and amulets were believed to have sacred powers. After the burial, a storm came along and churned up the waters and blew down all the trees. Lightening struck and melted the amulets. Cao Bien was so frightened he returned north, to China. Later administrators made offerings to the God of the Dragon's Navel.

After Vietnam became independent from China in the eleventh century, Ly Cong Uan (also known as King Ly Thai To) left his capital in Hoa Lu for what is now Hanoi. For a year and a half he tried to build walls for a new citadel, but because the land was marshy the walls collapsed. He renovated the former altar to the spirits of Long Do and To Lich and made offerings. In a dream a white-haired man appeared to the king and bowed and said, "Long live the King. I want this empire to last as long as the Thi Son mountain. " (Thi Son is a mythical mountain.)

Then, while the king was praying he was dazzled by the sight of a great white horse galloping west from the temple and leaving clear hoof prints. When it had encircled an area of land, the horse disappeared back into the temple. The king understood this apparition as an incarnation of the river god, To Lich, and took it as an omen to build the citadel on the ground marked off by the hoof prints. Indeed, the final construction remained intact. The king made the white horse the spirit of Thang Long and believed it would look after the country. In the course of history, the street has caught fire three times and all the houses were burned but the temple on the banks of the To Lich river always remained intact.

The temple, acknowledged by the state as an historic site, is a low building. On the tip of the roof are the traditional symbols found on Vietnamese religious structures: two dragons bowing to a flaming disk that represents the sun. The temple is composed of six buildings: a vestibule, a reception hall, the front sanctuary and several inner sanctuaries. From the street, one enters the vestibule where there is a large drum to the left and a bronze bell on the right. Next, one steps down into an open reception area. The fact that this section is lower than the street level reminds us that in the old days the building was on the riverbank. Later, to avoid flooding, the streets around the site were built up. In the reception hall, ladies often sit at a table gossiping, drinking tea and chewing betel nut after praying. A calligrapher sometimes sits nearby. He will write up a supplicant's wishes on special prayer notes. The notes are offered along with incense on the alter and burned in the fireplace. Also in this area is an altar for the mother goddess Lieu Hanh. The Bach Ma Temple has a miniature pond and mountain, common to many Vietnamese religious structures, which protect the temple from evil spirits.

The front and inner sanctuaries hold altars honoring Buddha. Although this was originally a Taoist temple relating to folk beliefs in primitive earth gods, Buddha has been incorporated into the pantheon. But this is not a pagoda. The term pagoda refers to a place where the main object of worship is Buddha. Behind the Buddha statue is the throne to Long Do. There is also an altar to three goddesses. The central one is red and is the Mountain Goddess, the one in white is the Sky Goddess, and the one in green is Goddess of the Waters.

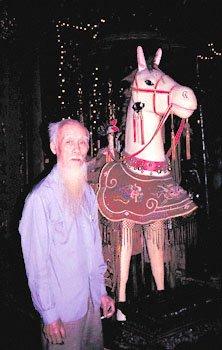

Further back in the temple the atmosphere becomes more sacred. Altars are lavishly decorated with offerings of flowers and fruit, incense burns sweetly. On the left of the altar is an ornately carved red lacquer palanquin. This honorary chair is used to carry the throne of Long Do. In the inner sanctuary, the White Horse God is honored in the form of a life-size wooden statue. Long Do and To Lich are represented by a brown-faced statue. On either sides of this altar are two amusing wooden statues of kneeling servants. Their arms are extended, holding incense sticks. The faces of the statues are dark brown, perhaps representing the fact that they might be Cham prisoners-of-war used as slaves.

Although it is not the largest nor the most beautiful of Hanoi's religious monuments, the White Horse Temple forms the historic heart of Hanoi and recalls the folklore of the city's founding. The temple stands on Hang Buom Street, a street once known as the home of sail-makers (buom means sail). A half block to the east of the White Horse Temple is the former Cantonese Association house, of distinctly Chinese style. Note the tubular roof tiles in contrast to the flat Vietnamese tiles. Other than the citadel, the temple is the oldest site in Hanoi and is known to have stood for over a thousand years.

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian