Hong Kong Duet-Voices of Old Hong Kong

Hong Kong's Chinatown

When you explore the western district of Hong Kong Island, you enter into a world of ladder streets and bird walkers, herbal medicines and fortunetellers, street barbers and snake markets. It is a tumbledown world of ramshackle slophouses, their goods spilling over into narrow lanes. It is an exotic, mysterious and alien world that has changed little since the first colonists arrived form China.

In the mornings especially, the lane markets are crowded and noisy, the narrow walkways made even more cramped by the overflow of merchandise. The overhanging awnings create a false twilight that is illuminated by light bulbs strung over the stalls. The souk-like shops purvey a motley assortment of products. Live fish are kept in tubs with hoses pumping in oxygen. Recently live fish are cleaned; their heads in a nearby pile are also for sale. There are mounds of vegetables and fruit and bunches of flowers. Sides of beef hang on racks as butchers hack and slice, weighing each purchase on a hand held balance scale. Tubs of live eels sit next to stacks of live crabs wrapped individually in ribbons of banana leaves; live frogs are jammed into cages like jellybeans. An egg vendor displays several varieties, including some unappetizing looking "thousand-year-old eggs" and preserved black salted eggs, both of which are considered to be great delicacies. Pressed ducks looking like deformed Frisbees hang in the windows by the hundreds.

Chickens in overcrowded cages squawk plaintively while vendors holler out prices and customers try to negotiate a better deal. A pushcart rigged with a hand-cranked press crushes sugar cane to produce a thick green liquid that is reputed to have a number of medicinal properties. An old woman squats in a doorway working meticulously at cleaning a mound of bean sprouts, a cigarette dangling from her mouth. A man alerts those in front as he wedges his four-wheel cart full of noodles through the crowd of people. Negotiating the alleyway with experienced steps, a birdwalker makes his daily outing. In a niche no wider than a meter, a barber works on his client who sits on a plastic lawn chair, smoking. The crowd parts to allow the passing of two men carrying a large gutted hog.

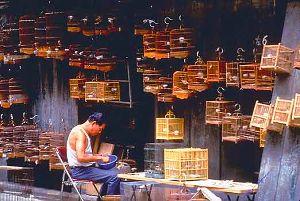

There is an energy here, a vigor, all is movement, all is bustle. Dai pai dongs, (small food stalls) are plentiful; the customers manipulate lengthy noodles with chopsticks, the bowls raised close to their mouths, apparently oblivious to the people at their elbows. One three-table outdoor dai pai dong is crowded with bird walkers who have stopped for tea and a game of mahjongg which they play with passion and intensity. Their birds hanging in rattan cages chirp and whistle, as if trying to out-sing each other.

Odors intermingle and grow with every step; there is a smell of earthiness and dampness, of fish and incense, cigarettes and tiger balm. On the plateaus of ladder streets, vendors are squatting in front of small blankets that display their wares. Many appear to be selling items found when cleaning out drawers'razor blades, packages of screws, the head of a hammer, rolls of string and ball point pens join sundry other odds and ends. Others sell dried roots and fresh herbs, ointments and medicated oils. One enterprising woman pitches her products over a battery-operated megaphone. Some vendors travel from place to place, looking for a propitious location to unfold their tables and sell copied watches, silk ties or leather belts.

A wizened fortuneteller sits smoking behind a card table in a small alcove. Behind him, taped to the wall, is a large and yellowing poster of a hand that has been sectioned off and labeled with Chinese characters. The entire tabletop consists of a chart with arcane icons and esoteric diagrams; booklets made thick by frequent reference sit next to a large magnifying glass. The old soothsayer stares at the table top as if contemplating the intricacies of ancient lore.

Steps away are a number of small cubicles with men carving "chops" out of ivory, stone and jade; the Chinese have used these seals with engraved names or initials for centuries. Another laneway has shops selling a variety of paper or bamboo effigies to be burned at funerals so that the departed are ensured a comfortable and happy afterlife. A calligrapher works at his streetside stall, red banners with gold characters hanging all around him.

Along another road there are numerous snake sellers'their products in an assortment of sizes and of various degrees of deadliness, are stacked in cages on the sidewalk awaiting their destiny as snake soup or snake bile wine. Jars containing whole snakes in a brown liquid line the shelves and counters; the potent tonic can be purchased by the cupful. In a doorway, a man slices into live snakes and tears out their gall bladders, dropping them into plastic bags held out by eager customers.

Herbal medicine shops that are located throughout the area display an astounding array of time honored remedies. A plethora of herbs, bark and dried insects are displayed beside horns, tails and other parts of animals. Thick black paste made from twenty different herbs and spices is used to make tea. Rows of wooden drawers hide exotic and bizarre curatives that have been used for a millennium to bring vitality, virility and longevity. Dried seahorses, silkworms, snakes, toads, centipedes and scorpions fill large bins. Dried deer tails are heaped into mounds. Another jar contains a score of baby mice floating in a clear liquid.

Potions and elixirs steep in bottles. One vendor happily revealed the ingredients of one particularly ominous looking mixture. Sprigs of herbs and pieces of bark are combined with a variety of dried insects, large and small. Ginseng and other roots are chopped into the brew as are the ground-up penises of five different animals. After an entire freshly killed snake is curled into the bottle and white wine is added to the strange menagerie, it was allowed to brew for 150 days. The resulting elixir, the pharmacist explained, should be taken in very small doses by men wishing to increase their sexual prowess. He grinned and made the universal gesture with his fist and forearm.

In the traditional medicine shops, complaints are analyzed, eyes are scrutinized, pulses are felt and tongues are examined before prescriptions from the vast pharmacopoeia are carefully weighed and scooped into ever growing piles on square pieces of paper arranged along the counter. Made into vile-tasting teas, the concoctions are sipped diligently, their efficacy well documented over the generations.

In the shadows of towering monoliths and shopping complexes, Hong Kong's Chinatown is a world apart. Laneways and alleys call out as you pass, each offering glimpses of traditions and customs that have remained virtually unaffected by the electric frenzy of contemporary Hong Kong life.

* * *

Hong Kong's Bird Walkers

It was early in the morning and the sidewalks along Nathan Road near Kowloon Park were temporarily not crowded. An elderly bird walker shuffled along, occasionally puffing on a nicotine-stained cigarette holder. He carried two birdcages, one hanging from the other. The birds offered tentative chirps as the cages swayed with the man's rhythm. When viewed against the backdrop of computers, video cameras and other electronic gadgetry in the windows, the reflection of the birdwalker created a brief allegorical montage.

The Chinese love birds; few apartments are without at least one songbird. Much like the nightingale allowed the poet Keats to escape "the weariness, the fever, and the fret" of life, the soothing wings of birdsong transcend the pressures of cramped, crowded living.

The custom of bird walking, an ancient Chinese tradition that is solely a male activity, is social in nature. To the Chinese, bird walking is considered very manly; birds are displayed with much pride and a melodic singer brings much esteem to its owner.

You will probably find Hong Lok Street by ear; located in Kowloon's Mong Kok area with easy access by the MTR, Hong Kong's modern and efficient subway system, "Bird Street" purveys exclusively to bird fanciers. The narrow lanes are jammed with stalls; the place rings with the twittering, warbling, chirping and whistling of thousands of birds of different species, sizes, and colors. Cages of finely crafted rattan and bamboo are on display as are little, ornately painted, porcelain water dishes. The variety of food available for the birds runs much further than mere seeds. Various sizes of live grasshoppers cling to the sides of mesh cages; crickets fill glass containers. Wiggling larvae are scooped into plastic bags and secured with twist ties.

A stop for dim sum is an essential component of the bird walking ritual; the few teahouses in Mong Kok that cater to bird walkers are always crowded and noisy in the mornings. Dozens of caged birds are suspended from rods and wall hooks. The birds appear to compete; their a cappella warbling and whistled arpeggios are incessant. A few men, their hands clasped behind their backs, appraise the birds, critically examining plumage, color and song. Some men read newspapers or drink tea, slurping and sucking loudly; some play mahjongg, the rhythmic clack of the tiles cracking through the clatter. Others talk, the singsong lilt of Cantonese like a choral reading of a tonal poem. Everyone smokes.

Later, in the MTR station, a man carrying a covered birdcage contrasted with the people around him like a black and white image in a color photograph. Serene and detached, he stood to the right as the escalator climbed to street level; suits with anonymous faces hurried by him, walking the moving stairs in their perpetual rush. A sense of balance rather than incongruity is seen. The blatant capitalism may provide the drive, but customs such as bird walking provide the solace.

* * *

How to Get There:

The Western District of Hong Kong Island, also known as Sheung Wan, is an area bounded on the north by the harbor, to the east by the Central Market area, to the west by the Tung Wa Hospital and to the south by Caine Road.

If you are coming from Kowloon on the Star Ferry, walk from the Star Ferry pier to Des Voeux Road and take the MTR to the Sheung Wan station.

If you are on Caine Road, you can enter the area down any of the "ladder streets" between Elgin Street to Hospital Road. A tram marked either "Kennedy Town" or "Whitty Street" is the most interesting way to Sheung Wan. Get off near the Western Market or when things begin to look interesting.

The Hong Kong Tourist Association (HKTA) provides a free walking tour booklet of the Central and Western districts, but perhaps you should trust in serendipity.

* * * * *

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian