In Awe Of The Landscape: Mountains and Machinations in Sikkim

What happens to a country that votes itself out of existence? This was the dilemma facing the people of Sikkim, when in 1975 they voted in a referendum to join the Indian union. “Who’s afraid of the big bad wolf?” asked those in favour of amalgamation, as they pointed warily towards the Chinese border, just an hour’s drive from the Sikkimese capital Gangtok. “Just about everyone” was the reply, with a vote of nearly 90% for integration with India.

Now, nearly 30 years down the track, feelings towards India are as contradictory as are the chaotic politics of this little state. At the time of my visit, electioneering was underway in Sikkim, and the Sikkim Democratic Front was fronting the absurd notion that it really IS democratic, in a country where votes are openly bought and sold like shares on the stock market.

But it was not hard to discern where people’s sympathies really lie. Even the official Electoral Office vehicles were plastered with stickers showing the Karmapa and Dalai Lamas together, with the slogan “Karmapa for Rumtek”. This slogan urges that the young Karmapa Lama, who escaped from Tibet in 1990, quickly be allowed to take up his seat at Rumtek Monastery.

Had the Chinese invaded Sikkim in the 1970s, they might well have achieved an economic miracle – but at what cost? The Sikkimese had only to look over the border to Tibet, where religious freedoms had been brutally suppressed. In the end, the Sikkimese people chose faith over food, and devotion over development.

Slow economic development HAS happened in Sikkim, but the natural obstacles are formidable. With 14 mountains over 6,000 metres high, this is one of the most rugged areas on earth. The foothills of the mountains are every year subject to disastrous landslides during the monsoon season. Whole villages careen down into the raging gorge-rivers, far below. The roads, too, are washed away with monotonous regularity. The Sikkimese are forced to divert a huge swag of precious resources to reconstruction, before development can even begin.

There is no such thing as a flat surface in Sikkim. When the authorities wanted to build a football field in the Western town of Namchi, they had to flatten a whole hillside just to get enough level ground. For the same reason, there is no airport in the state. What roads there are have to be laboriously carved through the hills, at inclines which often appear to defy gravity.

Gangtok, the Sikkimese state capital, lies in the district of East Sikkim. Getting to Gangtok from Bagdogra Airport (in adjacent West Bengal State) is a trip in itself, along a tortuously winding road, where gushing waterfalls rush over the lichen-covered rocks that line the roadside. En route, the road passes the huge new Manipal Institute of Computer Science and Technology, where students enjoy blissful views over the raging Teesta River (I couldn’t help wondering how they ever manage to devote themselves to study).

The city of Gangtok, now with over 200,000 residents, tumbles down the sides of a steep hill-ringed bowl that converges in a natural amphitheatre. Like a child grown too big for its clothes, Gangtok is now bursting at the seams, and is in dire need of an urban tailor to do ring-road alterations.

There are plenty of things to do in and around Gangtok, including just walking around town and drinking in the heady racial mix of Lepcha, Bhutia, Nepali, Tibetan and Indian people making up the city’s population. The exotic animal population of the region is showcased at the highly recommended Himalayan Zoo Park.

Pointing to a sign at the entrance to the zoo, the gatekeeper warns us not to have inflated hopes of actually seeing any animals. “The enclosures are very large in area,” says the sign, “having been constructed in line with the latest concept in ‘immersion exhibits’.” But a little effort in walking and waiting is amply rewarded, as I get to see the rare Himalayan Red Panda, the Himalayan Leopard Cat and the Himalayan Palm Civet. I DON’T get to see (but don’t particularly miss) the Himalayan Thar and the Himalayan Blue Sheep.

The name Ney Mayal Lyang or “heaven” is given to Sikkim by the Lepchas, the original inhabitants of the state. In Gangtok I meet up with Renzino Lepcha, Executive Secretary of the Ecotourism and Conservation Society of Sikkim. “No-one really knows where the Lepchas come from,” he says. “Many say that we are from different parts of Burma, with each Lepcha clan still worshipping a different Sikkimese mountain. And our language continues to be written in Burmese-style script.”

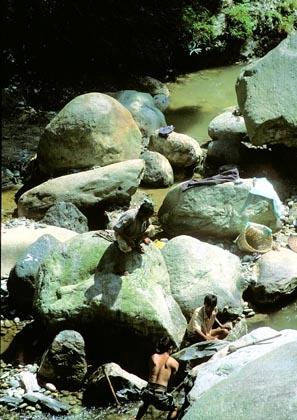

Whatever the origin, the Lepcha concept of heaven can amply be appreciated by taking a hair-raising trip to the district of Northern Sikkim. A section of the northern road sinks every year, just after the monsoon. A veritable army of workers breaks up granite rocks with lump hammers, placing the stones in chain-wire frames, which will form an embankment. The road is then arduously built up, the sub-surface stabilized and finally the tarmac repaired.

En route to the vilalge of Phodong, the site known as Kabi Longtsok marks the place where a blood brotherhood treaty was signed between the Tibetan and Lepcha chiefs Khye Bumsa and Tekong Tek, back in the 13th Century. The signing is said to have been witnessed by the holy mountain Kangchendzonga (no objection by the mountain is recorded, so the treaty must be genuine), thereby marking the birth of the nation of Sikkim.

Crossing a touch-and-go suspension bridge over the Raté River, we enter the district of North Sikkim. Lush greenery, mauve-flowering lasiandras, raging torrents through deep ravines – these are what make up North Sikkim. Home to the Bhutia nationality, this is a place where people wear Tibetan clothing, and yak-butter tea is standard fare at roadside cafés.

At Phodong Monastery, young monks are at school in an outdoor pavilion, chanting from a book of scriptures. The teacher seems to have mastered the art of keeping bored students awake. The chant slowly builds up to a crescendo, culminating in an exuberant “hoy”, like the roar of a football crowd when a winning goal is kicked.

Another day, I take the road to Western Sikkim, via South Sikkim. The road to Yuksom is hairier than anything previously encountered. The gorges seem to be a clone of the Grand Canyon, dropping sheer away from the roadside. On less steep hills, rice paddies stagger down to whitewater streams gushing far below. The biggest of the rivers, the Teesta, is being “tamed” by the giant new Teesta Hydroelectric project, which when completed will make Sikkim a net exporter of electricity.

In the district of South Sikkim, the little town of Ravangla (also spelt Rabongla or Ravongla – take your pick) looks like a leftover stage set from a 1950s John Wayne movie. The town is headquarters for the Dalai Lama’s Tibetan Army. All ten of the Army’s members are drilling on the parade ground. But it has to be said that the Army’s activities are low-key in the extreme, for fear of violating India’s hospitality.

Here in South Sikkim, even four-wheel drive doesn’t seem quite enough to handle the “roads”, all of which seem to have been built straddling fault lines. Near the sublime hilltop monastery of Tashiding, a vehicle loaded with crates of brandy has run over a cliff. Miraculously, no-one has been injured, but the driver has run away, presumably out of fear of legal action.

Yuksom, coronation site of the first Chogyal (king) of Sikkim, is primarily a trekking base, consisting of a few houses and cafés, a slightly greater number of yaks, and bemused locals languidly spinning prayer-wheels. The skies have been depressingly leaden, but early one morning the clouds miraculously part, affording a mind-blowing view over Sikkim’s second highest mountain, Mount Kabru. The daddy of them all, Mount Kangchendzonga, is best viewed at Pelling, a town just 20 km from Yuksom, via a quasi-road road through spectacular bamboo forests that drop sheer away to the Ratong river gorge.

In just four or five years Pelling has become an important tourist centre for visitors from all over the Indian sub-continent – particular during November, when the views over Mt Kangchendzonga are at their best. Pelling is also home to Pemayangtse Monastery. I climb a rickety wooden staircase to the top level of the monastery, where a seven-tiered carving Zangdoplari, by master sculptor Dungzim Rinpoche, fills the whole room. The sculpture, with its rich and finely-wrought detail, is said to depict the architectural layout of heaven.

Heaven is also said to be epitomized by nearby Kechopari Lake. But I never did get to see Kechopari. Politics once again intervened.

“There’s been an assassination just over the border in West Bengal,” came a telephone message. “All the roads out of Sikkim are closed. We have to go straight back to Gangtok.”

I had intended to leave Sikkim via the western border town of Jorethang, but to no avail. Finally, it was not the vagaries of nature that stymied the end of this trip, but the whims of politicians. And it is hard to know which of these two is the more capricious!

* * *

Fact File

Currency: Indian Rupees. One US dollar equals about 48 Rupees.

Getting There: The excellent Indian domestic airline Jet Airways flies regularly from Delhi and Kolkata (Calcutta) to Bagdogra, from where Gangtok is 30 minutes by helicopter (this service is heavily subsidized by the Sikkim Government, costing only $US16 one way). For helicopter bookings, contact Namgyal Treks and Tours (see below).

Accommodation:

Gangtok: Nor-Khill, the major heritage hotel of Gangtok, is excellent, with authentic Sikkimese ambiance – if, that is, you can stand the Raj-era mock deference accompanying the service. Tel +91-3592-25637, fax: +91-3592-25639; email : norkhill@sify.com; see also http://www.elginhotels.com/norkhill/norkhill-about.html

Rumtek: Shambala Tourist Resort (+91 3592 52240 or 52243) has tourist huts in traditional Lepcha, Bhutia and Nepali style.

Pelling (West Sikkim): the Norbu Ghang Resort (tel +91 3595 58245 or see http://sikkiminfo.net/norbughang/ ) is highly recommended, with great mountain views, and excellent Sikkimese cuisine.

Tour Operators:

Namgyal Treks and Tours is excellent, with a wealth of expertise throughout Sikkim, Bhutan and Tibet. Contact details: Tibet Road, P.O. Box – 75, Gangtok - 737101, Sikkim, India. Tel :+ 91-3592-23701 / 24924 / 27027, Fax : +91-3592-23067, e mail : slg_trekking@sancharnet.in. See: http://www.indiamart.com/namgyaltreks/

Guide-books:

Sikkim : A Traveller's Guide by Arundhati Ray, Sujoy Das (ISBN: 8178240084, available through Amazon.com) has superb photography but somewhat woolly text.

Sikkim: a Guide and Handbook (April 2002) is extremely comprehensive, but available only in Sikkim, at a cost of Rs 88 (about $US1.80). Try writing to the author Rajesh Verma, at Verma Building, near Police Headquarters, Gangtok 737101, INDIA.

Further Info: Government of India Tourist Office, tel (02) 9264 4855

* * *

Acknowledgments: The author visited India as a guest of the Government of India Tourist Office.

* * * * *

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian