The Day The Music Died: East Timor Re-Visited

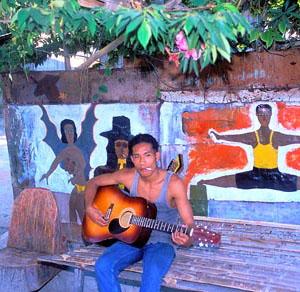

East Timor is a musical country. The music of the Portuguese fado blends with the techno-beat of Indonesian rock; guitarists practice by the roadside; an office building in a suburb of the capital Dili is decorated with a triptych of musical instruments.

But on 4 September 1999, the music died. Immediately following a massive vote for independence in a referendum unexpectedly granted by Indonesia's President Habibie, anti-independence militia ran amok, burning and destroying on a massive scale. What remained of the population fled to the mountains, leaving the empty, burnt out remains of Dili and other towns and villages. By the time that the militia had spent their rage, over 80% of Dili's buildings lay in ruins.

Miraculously, the music that died in 1999 started up again on 20 May 2002, with the declaration of the country's independence. Now, with rebuilding proceeding apace, intrepid visitors to this brand-new nation have the opportunity to explore at will. Security is no longer a problem, though visitors are still advised not to venture too close to the West Timorese border.

My thoughts drifted back to pre-Indonesian Timor. In 1973, the main road between Dili and Baucau (then East Timor's two biggest "cities") was little more than a rutted goat track. On the back of a clapped-out truck, it took me over eight hours to reach Dili, along dry riverbeds and along roads so corrugated they could have been used to pack beer.

What little education then existed in East Timor was provided only by the mission schools. There was only one very rudimentary hospital. The Portuguese seemed to believe that the Timorese deserved neither an education nor decent health.

Is it any wonder, then, that I became one of the silent majority that acquiesced in the Indonesian invasion of 1975? Along with most others, I believed that the Indonesians could not be worse colonisers than the Portuguese. The subsequent 24 years proved this belief to be wrong.

So it was with a little trepidation that I returned to East Timor in June 2002. The night before departure, I was anticipating this journey of rediscovery more than any other. My knowledge of what is still the lingua franca (Indonesian) was as rusty as a Pommy bath-tap, and I didn't quite know what to expect upon arrival; except for one thing...I knew I would be mightily moved.

This indeed proved to be the case. I was moved by the upbeat attitude of the people, who despite heavy personal losses don't seem to harbour any grudges. I was moved by the total commitment of the international community, who despite some criticisms (most notably by journalists who never venture out of Dili) are moving heaven and earth to get East Timor working again. And most of all, I was moved by the attitude of the young Timorese, who are demonstrating the thirst for education and the entrepreneurial skills that will be vital in building economic independence.

João, a young taxi driver in Dili, typifies the equivocal attitude of the Timorese people towards the Indonesian invaders. "Three of my seven brothers and sisters died during the Indonesian occupation", he says. "But the Indonesians also did a lot of good, building roads and schools and so forth". As elsewhere in East Timor, the spirit of reconciliation seemed to come naturally, being heart-felt rather than a forced response.

Liu da Silva's story is another from the unwritten book of "incredible journeys". Born in East Timor and educated in Jakarta, he had to be smuggled out of Jakarta to Lisbon, at great personal expense, due to suspected involvement in student activism. Subsequently, after several years in Darwin, he eventually returned to his homeland. "The Portuguese were OK", he says, "but they had too many colonies. That's why they never had the money to develop East Timor."

The coastal road to Baucau, East Timor's second city, shows more evidence that the music is now returning. Both locals and expat volunteers relax at the weekend under what remains of the beach shelters at "Dollar Beach", 38 km from Dili. The name refers to earlier UN days, when you could have the whole beach to yourself for the day upon payment of a dollar to the local community. But now, in the new East Timor, anyone is free to swim in the crystal-clear waters, or snorkel among the soft corals that lie just of the beach.

In the near-destroyed town of Manatuto, fine wall paintings decorate the walls of one of the few remaining civic buildings. A Timorese warrior bearing the flag of the newly independent nation rides on a crocodile, a traditional folk emblem. In the village of Laleia, with its fine Portuguese cathedral, the East Timor flag rises above a map of Timor resting on a bed of skulls. From death, life has re-arisen.

In the city of Baucau, where I had walked down to the beach in 1973 in the company of Portuguese conscripts who then regarded Timor as the "crème-de-la-crème" of foreign postings, the locals are determinedly rebuilding their lives. The notorious Hotel Flamboyan, its back rooms once used as torture chambers by the Indonesian Army, has been gutted and totally rebuilt, in lavish Portuguese pousada style. The new Pousada de Baucau was inaugurated by the Bishop of Baucau in March 2002.

When the famous travel writer Norman Lewis visited Baucau in 1991, he described the city as "one of the most disturbing places in the world,... a dishevelled town full of barracks and interrogation centres with high, windowless walls and electrified fences. Baucau had been the end of the road for so many real and assumed supporters of Fretilin".

Today, many parts of Baucau are still in dire need of rebuilding. Ransacked buildings include the fine old Portuguese-style Mercado Municipal (municipal market), with its Roman-style forum, and nearly all the office buildings. But you can now drive right down to the beach, a fine sand-fringed lagoon where colourful fishing boats ride at anchor. Or take in the colourful local market, held under a giant banyan tree that was one of the few things to escape the wrath of the retreating Indonesians

Another day, I head out of Dili towards the rugged hills that fracture the countryside. The trip takes a little longer than expected, as the road is a graveyard for careless drivers, twisting and turning upon itself like an itchy snake. My own vehicle is merely run off the road by a bus and later suffers a blowout; others are not so lucky. On one blind corner, I'm greeted with the sight of a timber jinker that has plunged over the edge to a resting place 100 metres below. "It's a miracle that no-one was killed", says the English manager of the NGO that owns the truck. "I told them not to drive when they are drunk!"

Other requisite stops include photo opportunities, stops to ask directions, and the obligatory gape-break, when the totally amazing presents itself - such as a warrior-clad cowboy with Che Guevara medals on his chest, riding a pony along the roadside. In this region, altitude means attitude.

The cool highland town of Maubisse is an area of great scenic beauty - a hill station that never rises above its station. Home to the local Mambae people, the town has an excellent mountaintop pousada, offering plush accommodation. The community church may offer some clues as to why the Timorese are such devout Catholics. In few other countries has the Church managed so thoroughly to accommodate itself to the indigenous beliefs of the people. Outside the church stands a totem pole studded with buffalo horns, just one of many symbols of the lulic animist faith, which combines belief in spirits with ancestor worship.

Above the marketplace of of Maubisse, a simple cross in the town cemetery is a poignant memorial to three decades of conflict between all three factions in the Timorese civil war - the Fretilin independence movement, the pro-Indonesian forces and the pro-Portuguese faction. As it turns out, independence has resulted in something for everyone. Portuguese is now the official language but spoken only by the elderly; Indonesian is de facto the national language; the indigenous language Tetum is spoken by everyone but not very useful internationally; while English is definitely a fourth-runner, but demanded by many employers.

Among the Timorese elites there is a tremendous commitment evident just now - a commitment to a bold experiment in nation-building. Palmira Pires, a native of East Timor who grew up in Melbourne but has now returned to Dili to head the East Timor Development Agency, says of her newly independent homeland: "East Timor means identity. All these years, we were identified as either Portuguese, Indonesian or Australian. Now, it is important to work towards one goal: to give back to the Timorese people the right to decide their own future."

Back in Dili, just a short distance across the sometimes-turbulent waters of the Wetar Strait can be seen the island of Ataúro, a former penal settlement where field-workers from Australian Volunteers International are now building an eco-tourism resort. This island was used by the Portuguese as a prison for Timorese and Portuguese troublemakers and activists from their African colonies of Angola and Mozambique. The Indonesians used Ataúro as a place of exile for families and supporters of anti-integration forces in the 80s. Among the treatments meted out to dissidents was the "coffin" - a narrow box-sized cell where prisoners were confined for months at a stretch.

Today, Ataúro is a peaceful refuge, with great snorkelling and diving on a reef just 50 metres of the beach; hot-springs, walks to native villages and sacred sites that have yet to be fully explored. Some rustic cabins are under construction. However, getting to Ataúro is still an exercise in "waiting for Godot". When the community ship Maun Alin pulls irregularly into Dili Harbour, she may stay only a couple of hours before turning around again, at maybe one or two in the morning (to take advantage of favourable tides). A more reliable option is the new ship Sea Emperor, which makes a return run every Saturday. But with this option you get only three hours on the island - scarcely long enough to even begin to explore. A not-very- satisfactory compromise is to go with the Sea Emperor, then take your chances on getting back again.

While travel in East Timor is still definitely an adventure, these are exhilarating times to be in this brand-new nation. Palmira Pires' brother, Alfredo Pires, is intensely moved by what he sees happening in East Timor. "You can see the potential here", he says. "You can smell it in the air; you can feel it in your bones."

After this, what more can anyone say? Excuse me a moment, while I close my eyes. I think I can hear a new symphony in the making.

* * * * *

Fact File:

Getting There: Air North (http:///www.airnorth.com.au ) flies 2-3 times a day from Darwin to Dili. With Air North, you can save up to 50% with 14-day advance purchase. To Ataúro Island, the new ship Sea Emperor has a return service each Saturday; for bookings contact Octagon Shipping, tel +61 409 642 762.

Telephones: There are two parallel telephone systems - Australia's Telstra mobile service and the (unreliable) numbers using the East Timor international code +670.

Money: The currency is US dollars. Cash advances can be had from ATMs at the ANZ Bank and the Hello Mister supermarket (in Rua Avenida Bispo de Medeiros).

Where to Stay:

Dili: There are basically three types of hotels:

The old standards such as Hotel Turismo (tel +61 408 081 326) and Hotel Dili (tel +670 390 313 958, fax +670 390 313 081), are now a little run-down. However, with the ongoing departure of the UN, rooms can now be had from around $US25.

Budget hotels. One recommended establishment is Hotel Purple Cow, on Pasir Putih Road (Meti'aut Beach). Rooms are a little spartan, but fully air-conditioned, and there is a great bar and restaurant on the premises. Rooms $US15 per night. Tel +61 409 502 798.

There are a couple of newer hotels catering to business and government visitors, with international-standard rooms from $US50-80. Try the Hotel Audian, tel +670 390 323 080, E-mail enquiries@hotelaudian.com. The main drawback is that these hotels are a long way from the waterfront and the city centre.

Maubisse: Pousada de Maubisse, book through Ensul Resorts, tel +61 438 890 096; $US30-40 weeknights, $70-80 at weekends.

Baucau: Pousada de Baucau, $US49 a night. Call +61 418 176 003 and leave message - or just turn up (it's a huge hotel, with plenty of vacant rooms).

Ataúro Island: The NGO Roman Luan, with aid from Australian Volunteers International, is building an eco-resort, with as yet just basic camping facilities. However, a cabin will be completed by July 2002, with several others in the pipeline. Contact Lisa and Michael Gilles on +61 417 707 583 (leave an SMS message).

Hire: It is best to stick with a reliable operator such as Thrifty Car Rental (near the waterfront, tel +61 419 61 9911, fax +670 390 321 078), from where reliable vehicles can be hired from $US35 a day.

* * * * *

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian