The Valley of Kathmandu - 3

Part 3 of 3

"Namaste," the waiter said as he bowed his head and pressed his palms together below his chin. We had heard the Nepali greeting frequently, although it was seldom accompanied by the respectful gesture; used as a general greeting or farewell, it literally means, "I salute the god within you."

We were having a late lunch in the garden patio of our hotel, The Malla, where it seemed, we were the only guests. Deciding to sample local food, we had a thick spinach and lentil soup, unleavened bread called naan, and the national favorite mo-mo, dumplings made from buffalo, chicken, or goat. The waiter served a large bottle of Star beer as if it was wine, first displaying the label with its snow mountain logo and then pouring a sample for tasting.

* * * * *

At a street corner in Thamel, a raffish area which has replaced Durbar Square as the main tourist enclave in Kathmandu, a driver of a peddle-powered trishaw lounges and smokes in the passenger seat, ever vigilant for customers. Above him on the posts are advertising signs, arrows pointing the direction to guesthouses, restaurants, trekking supplies shops, a massage clinic, a pizza house, and an authentic Bavarian deli. When a potential client approaches, he jumps down, his eyes smiling and hopeful, while gesturing gracefully at his vehicle.

Shophouses of two or three stories are crammed along the streets of Thamel, their goods displayed from the walls and spilling into the street. It is impossible to walk by a shop without a sales pitch. "Namaste" the shopkeepers will sing as they beckon at you from the doorway. "Come in and look at my carpets. No charge for looking. Where you from? Very cheap price. Come in! Have a look!" If you continue walking, they will try a different approach. "Change money? Good rate!" Just before you're out of whisper distance, new products are hawked; hashish, marijuana and opium are offered, sotto voce.

The narrow streets of Thamel can be hectic and chaotic as trishaws, motorcycles, bicycles, tuk-tuks, and cars, bells ringing, horns honking, buzzing and beeping incessantly as they compete with walkers and beggars and strolling street vendors. The air is thick with the smell of exhaust, incense, and mothballs. With nauseating frequency, someone will retch, cough raucously, and spit forcefully. If you show any interest in a street vendor's wares, and saying no is interpreted as a sign of interest, the vendor will wage an unrelenting siege, pleading, cajoling, nagging, and repeating like a mantra, "How much you want to pay?" Walkers, hawkers, hoikers and gawkers -- all become threads in the changing tapestry of the horn-tormented streets.

* * * * *

According to legend, the builders of the massive Buddhist stupa Baudhanath collected dew to mix with mortar since it was constructed during a period of severe drought. A world heritage site, Baudhanath is located along the silk road three and a half miles east of Kathmandu, on a site that has been sacred for 2500 years.

It's difficult to shake the feeling that you are being watched as you approach the stupa along the narrow lane crowded with vendors. From atop the imposing dome, the all-seeing, all knowing eyes of the Buddha watch over all. The stylized eyes are found on all Buddhist stupas, surveying all, protecting with omnipotent benevolence.

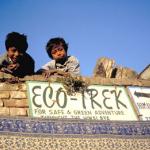

As we walked the centuries worn octagonal base inset with scores of prayer wheels, two kids aged about five and seven dogged our steps like puppies, selling wooden flutes that resembled miniature Gattling guns. Alternating between tugging at our shirts and playing plaintiff melodies, they would repeat the refrain "How much? How much?" over and over and over again.

As we were leaving, wending our way through a crush of vendors selling color slides and postcards of the stupa, the older of the two children ceased the monotonous repetition and holding out the flute, whispered with wide eyed sincerity, "Please buy; it's magic." His younger brother nodded with conviction. Desperation driven, there was not a smile from these children without a childhood.

* * * * *

The stupa Swayambhunath, said to contain the mortal remains of Gautama Buddha, is one of the holiest Tibetan-Buddhist shrines in Nepal. Built about three hundred feet above the Valley floor, the ancient Swayambhunath site has its origins in mythology.

"There is an interesting legend associated with this stupa, if you would care to hear it." Diwakar paused, cleared his throat, paused again, took a breath, and assured of our attention, outlined a story which linked the creation of the stupa with the creation of the Kathmandu Valley. "It has been said that the valley was once beneath a primordial lake. Manjusi, a Bodhisattva, used a magic sword to slice an opening in the mountains to the south, allowing the lake to drain via the Bagmati River. As the lake drained below this hill, a lotus took root here and burst into flame, indicating where to build the temple."

Rather than climb the long and steep stone steps to the shrine, like those on a pilgrimage, we drove to a plateau near the top and then walked up a pathway shared by begging monkeys, and cajoling vendors; one determined vendor tried to sell us a curved, wide-bladed Gurkha knife, beseeching all the way up, pleading all the way down when we left. "Watch your step," cautioned Diwakar. There were dogs everywhere.

In addition to the domed white stupa, dabbed with yellow to resemble a lotus flower, there are many smaller stupas, chaityas, some containing the remains of holy men, others relics, mantras, and holy writings.

Although the hilltop stupa is often praised for its panoramic views of the valley and awe inspiring glimpses of the snow mountains, a thick covering of fog and pollution hid the vista below and clouds shrouded the Himalayas. Still, the penetrating eyes of the Buddha watched over the valley from the base of the spire, protecting and blessing. The thousands of multi-colored prayer flags flapped in the wind, delivering their orisons to the abode of the gods.

* * * * *

A common item sold by vendors lends geological credibility to the fact that the valley was indeed once under water. Shali-gram stones, found near the Tibetan border, are cleaved to reveal aquatic fossils; the halves are held together with an elastic band and sold as mystical Tibetan sermons in stone, preaching scriptures from before language. Diwakar recommended that we purchase stones that had not been split, suggesting that the stone could be used as a focus for meditation and that the spiritual vibration would be unified and undiminished. "You know that there is a fossil within the stone and that it is millions of years old. There is no need for proof of the truth." Before our minds could delve into the intricacies of this metaphor for the spirit within all, the vendor offered his own philosophical suggestion, "Put it under your pillow; it will assure good dreams."

* * * * *

At Diwakar's urging and despite much skepticism, we visited the sanctuary of Rimpoche Awtari Lama, a spiritual teacher who divided his time between a monastery in the foothills of the Himalayas and Darjeeling, India. We passed through a security gate, walked a garden pathway, and arrived at a simple two-story house. A stereotyped image of an elderly Tibetan mystic with a shaved head, expounding on his insights into the meaning of existence was interrupted when we were invited upstairs to meet the lama.

He was about thirty and sat on his bed in the lotus position, wrapped in a reddish-brown robe. His long hair was clasped in a bun on top of his head; his eyes were gentle and kind and serene. As he answered our questions, his hands manipulated a string of beads. The room had all the sanctity of a cathedral, solely by his presence. We took a portion of his imperturbable transcendence and soothing gentleness away with us, and it will always be there to draw on, like a well.

"I think he is near the end of his spiritual journey," Diwakar observed as we left through the garden. We wondered how many incarnations were necessary to attain such serenity and equanimity.

* * * * *

We were at Dhulikhel, a small town eight miles east of Kathmandu, at the Himalayan Horizon, a secluded hotel that provides breathtaking views of the snow mountains. The vibrant green terraced rice fields formed a hushed amphitheater while remote and aloof, the Himalayas blazed in white-fired intensity.

"The home of enlightened souls," Diwakar announced, gesturing as if making an introduction. There was a thread of coldness, a wisp of frozen eloquence, as the souls replied.

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian